On Easter Sunday 2019, seven suicide bombers attacked busy tourist hotels and packed churches in the Sri Lankan capital Colombo. More than 250 people were killed, including many foreign nationals, and over 500 sustained injuries in the blasts. The coordinated assault was carried out by members of a newly formed radical Islamist group, with links to Islamic State (IS), which later claimed responsibility.

A fortnight later, the long-running Gaza-Israel conflict escalated when two Israeli soldiers were injured by sniper fire from the Gaza Strip, which is governed by the Hamas organisation. Retaliatory Israeli airstrikes resulted in several hundred rockets being fired into Israeli-held territory by several groups, including the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, the military arm of Hamas. There were further casualties on both sides, until Egyptian mediators negotiated a ceasefire.

On both occasions, reports soon emerged in the media about the use of cryptocurrencies to fund terrorist activities. IS was believed to have channelled sizeable sums to the Sri Lankan cell, raised through donations from anonymous and untraceable sources around the world. The al-Qassam Brigades groups openly invite cryptocurrency donations, broadcasting a step-by-step YouTube video on its website, including helpful tips to avoid detection.

Above: Members of the terrorist militant group, Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)

Cyber security?

“We’ve been tracking this push into cryptocurrencies for the last two years,” explains Steven Stalinsky, executive director of the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI), based in Washington DC, which provides research on Islamist organisations threatening the West. His team spends many hours every day monitoring groups that educate and preach jihad and martyrdom in mosques, schools and the media. In 2006 MEMRI launched their Cyber & Jihad Lab. “It studies how terrorist organisations use technology to fundraise, communicate and recruit new members,” Stalinsky adds. “Cryptocurrencies are a continuation of that.”

Credit: Fred Moon, Unsplash

The collapse of IS’s caliphate, and the marginalisation of other jihadi and terrorist organisations have created an increasing dependency on online finance. “The most significant and dangerous recent development in global terrorism is their embrace of cryptocurrencies to fund their activities,” said Stalinsky. “This has quietly become part of their cyber arsenal, and to date there has been a lack of understanding of how to stop it.”

While terrorist organisations have different causes – often conflicting – they will still learn best practice from each other, especially when it comes to communication or fundraising technology. “Whether it’s the Muslim Brotherhood, IS, Al-Qaeda or Hamas, they’re all facing a similar squeeze on their funding as the traditional channels are closed off,” says Stalinsky. The old smuggling routes are now more closely monitored by satellites and drones, while electronic bank accounts, as well as platforms such as Apple Pay and PayPal, are heavily regulated. Banks face huge penalties if they don’t comply. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies such as Dash, Ethereum, Monero, Verge and Zcash are very easy to use, but a lot harder to trace and disrupt.

How do virtual currencies work?

Bitcoin is the most widely used cryptocurrency. Instead of notes or minted coins, every bitcoin is a computer file that’s stored in a digital wallet app on a smartphone or computer. Bitcoins can be sent from one person to another, with each transaction recorded on a public list called the blockchain, which provides an immutable ledger. The blockchain only records numbers rather than names – and isn’t controlled by a government or bank like the US dollar or euro. So, although the amounts of transactions can be watched, it’s impossible to know who is transferring bitcoins to whom, unless they tell you their account number. Which they won’t. In any case, groups can receive the money, close that wallet and open a new one, in just a few swipes.

Following the money is largely futile, so governments need to disrupt the machinery instead. They are looking to put pressure on the owners, technology providers and exchanges – in the same way that social media owners are taking responsibility for outlawing violating content. Facebook, for example, tightened its own regulations following the tragic deaths of 51 people in New Zealand in March 2019, when a lone gunman live-streamed his rampage through Christchurch mosques.

Stalinsky believes cryptocurrencies need to learn the lessons of Christchurch. “In the early days of social media, companies, particularly Twitter, YouTube and Google, waited too long to address terrorist usage of their services. To ensure the same mistakes aren’t repeated for cryptocurrencies, it’s vital these companies put in place – now – clear policies banning criminal cryptocurrency activity on their platforms, with repercussions and penalties for companies that do not do so.”

Credit: Andre Francois McKenzie, Unsplash

There was some good news recently for counter-terror agencies, when the launch of a new cryptocurrency by a cloud-based messaging service was delayed. Stalinsky suggests it would have proved “very convenient for terrorist groups”. But, as he explains, unfortunately there are plenty of other cryptocurrencies and messaging apps that terrorists can use. “The authorities are always two steps behind in terms of technology.”

Not just Islamist groups

The other problem that Western authorities face is that it only takes one or two smart people to educate the rest. This was something that the (now deceased) IS military commander Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi recognised when he recruited technology, media and translation specialists to spread his vision for an Islamic caliphate in the Middle East. With the use of tutorials and social media, the leaders can reach a large number of followers.

“We shouldn’t see this just in terms of radical Muslim groups though,” adds Stalinsky. “There is emerging evidence of white supremacy groups in the US using cryptocurrencies to attract funding. This is happening in our backyard too.”

Stalinsky has an uneasy feeling about the harm that cryptocurrencies might cause in the future. He says they’re just “dabbling” at the moment, but it won’t be long before they increase their activity if they’re allowed to. “For example, cryptocurrencies offer a gilt-edged opportunity for IS to circulate the millions of dollars it has allegedly stockpiled from oil money during the height of the caliphate,” he adds. “They now have a channel to fund their fragmented networks across the world, providing money for surveillance and operations. They can keep the network alive and active. That’s worth worrying about.”

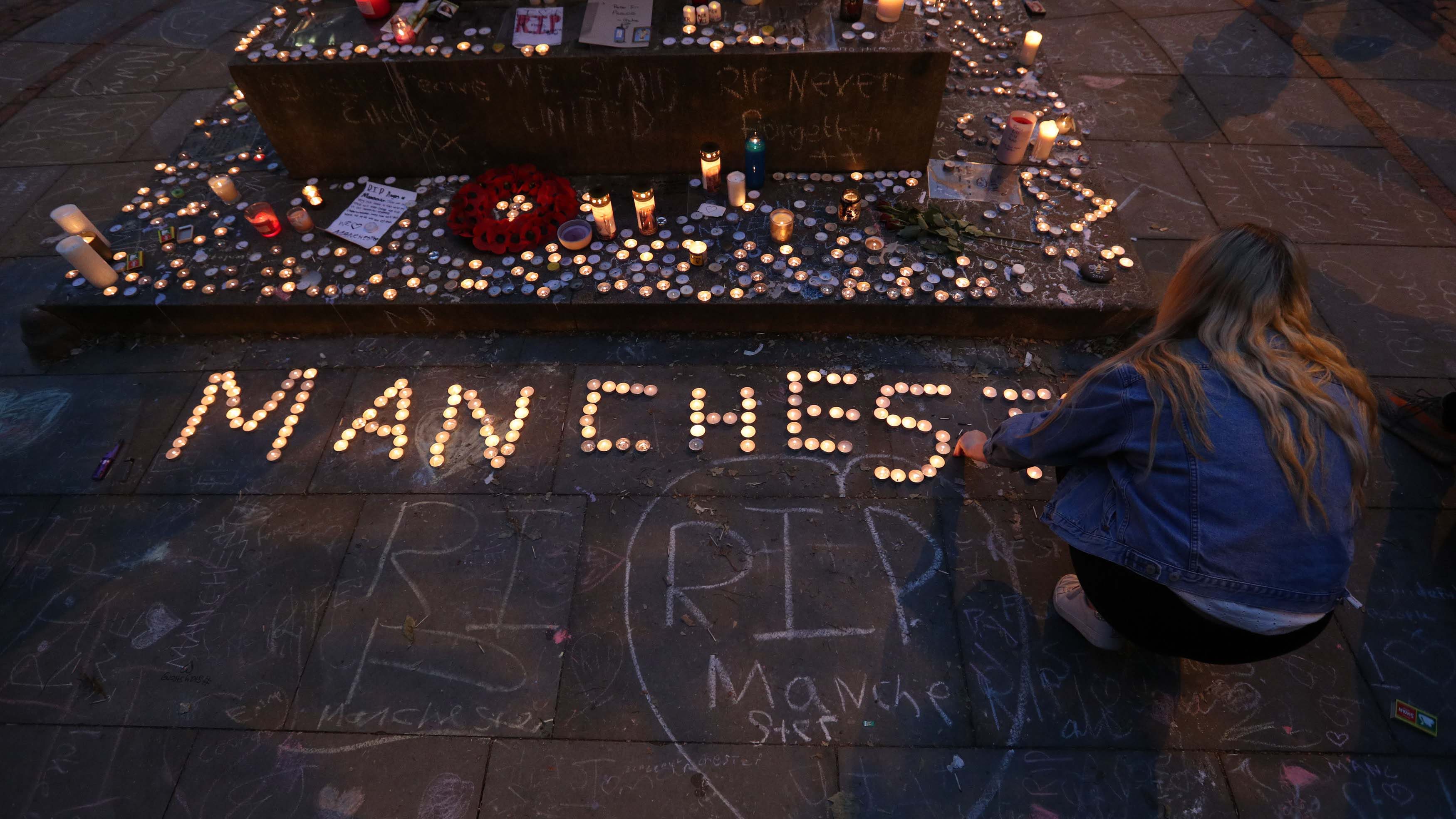

- Tributes to the victims of the Manchester Arena attack. null

- The Manchester Arena attack, 22nd May 2017. null

- Specna arms. null

- Credit: Nahel Abdul Hadi, Unsplash null