While art heists can often be exciting and glamorous, the subsequent attempts to sell the stolen goods are anything but.

By Noah Charney, founder of the Association for Research into Crimes against Art.

Back in 1988, at the elegant Colnaghi Gallery in New York, thieves smashed a skylight and rappelled down four stories, before snatching 19 paintings worth more than US$6 million, including a Fra Angelico and a Tintoretto.

In December 2000, in the Swedish capital Stockholm, car bombs detonated at various remote points across the city, drawing the police who believed it was a terrorist attack. In fact, it was just a diversion, as thieves drove up the peninsular road leading to the National Gallery, leaving behind them a trail of spikes to burst the tyres of would-be pursuers. They leapt out of their vehicle wearing balaclavas and wielding sub-machine guns, rushed into the open museum, shouted everyone to the floor, and made off with several paintings, including a Rembrandt, escaping in a speedboat in the bay behind the museum.

These escapades sound like they’re straight out of Hollywood movies: derring-do, a splash of art-world glamour, and more than a bit of sleight of hand. But are real-life art thefts ever quite as elegant, smooth and alluring as their silver-screen incarnations?

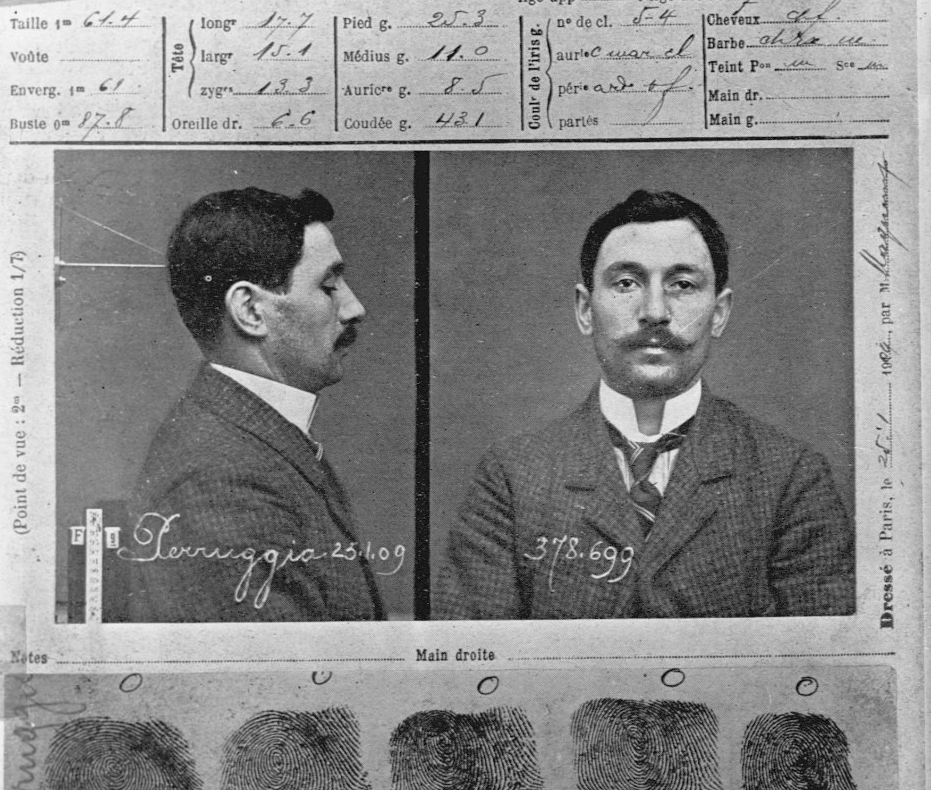

Extracting art from museums, private homes, galleries, bank vaults and churches is, believe it or not, the easy part. The thieves are occasionally fascinating characters, such as Vincenzo Peruggia, the Italian who stole the Mona Lisa in 1911, or Adam Worth, an American who stole Gainsborough’s Portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire from a London gallery in 1876. But most of the time they are simple criminals with no interest in or knowledge of art. They’ve seen the same films we have, and therefore have romanticised ideas about how art crime works.

Above: Vincenzo Peruggia

Above: Mona Lisa, by Leonardo da Vinci

So while the heists can be cinematic, what happens to the stolen goods afterwards is far more prosaic. Stolen art essentially has no market at all, particularly now, in the age of the Internet, when anyone can check online databases as to whether a particular work is hot or not.

It is extremely difficult for criminals to profit from their hard-stolen goods. Some works are ransomed, but if a ransom goes unpaid then the criminals are out of luck, as they often have no plan B.

Mid-to-low-level works can sometimes be sold since they are less renowned, but recognisable works have no ready buyers. Criminals believe that illegal collectors like the fictitious Thomas Crown (from The Thomas Crown Affair) or Dr. No (from the James Bond movie) really exist. But in the true history of art crime there are just a few dozen such examples over the last century – a tiny number, when one considers the tens of thousands of art thefts reported each year, and the many more that go undiscovered or unreported.

Instead of selling on their stolen art to criminal collectors, thieves often end up falling for undercover police officers. Indeed, this was how the Stockholm Rembrandt was recovered, eventually offered to a policeman in disguise.