Dr Helen Scales is a marine biologist and broadcaster who teaches at Cambridge University. In her new book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, she reveals the mysteries of the deep oceans – their fantastic creatures and fragile eco-systems – and explores the tension between scientists who wish to study this little known region of the planet and the industrialists who wish to exploit it.

Scales says we are living in a golden era for deep-sea exploration. “Technologies developed over the last decade are hugely advancing our ability to see into the deepest depths of the ocean and conduct experiments,” she tells Chart magazine. “There are deep-diving submersibles, controlled from the surface and decked out in cameras, videos and all sorts of sensors and devices. The subs have robotic arms, so it’s possible to collect specimens of organisms, sediments, water and rocks. It’s obviously less risky and not as expensive as sending people into the deep in submersibles.”

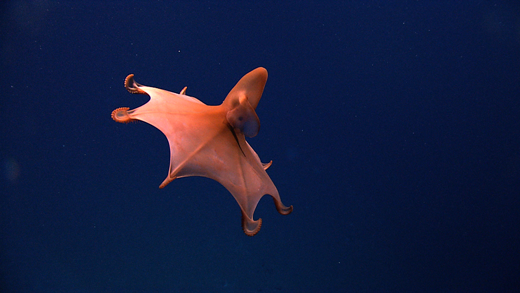

Scientists also use self-guiding submersibles, programmed to navigate the deep ocean for long periods, gathering data all the while. “These are amazing tools for mapping the seabed,” says Scales. “A single machine can take millions of photos on a single dive, which can then be stitched together into a high-definition photo mosaic. This shows the physical features of the seabed, and also surveys large organisms, like fish, octopuses and corals.”

Scales admits the conservation of the deep oceans is a difficult task since the general public knows, and cares, so little about it. “The deep is the most extreme case of out of sight and out of mind. However, a lot of people are inherently fascinated by the deep sea, in a similar way that we find space exploration compelling. The strongest advocates for the deep sea are the scientists who work there and they are doing an amazing job of bringing the deep into view with the budgets they have.” She points to vital research institutions such as the Ocean Exploration Trust and the Schmidt Ocean Institute, as well as recent documentaries.

“I think things are moving in the right direction to bring the wonders of the deep into public view,” she adds. “But more funding needs to be devoted to understanding and spreading the word about this critical part of our living planet.”

Here are the most intriguing facts we discovered while reading Scales’ new book.

- There are very few full-time scientists working in deep-sea marine biology – perhaps 500 or so. “If the entire deep-sea realm were divided up equally between them, each would get roughly two million cubic kilometres of ocean to study,” writes Scales.

- The ocean is divided into five separate zones: the sunlit zone stretches from the surface down to 200 metres; between 200 and 1,000 metres is the twilight zone; then the midnight zone, down to 4,000 metres; below that is the abyssal zone, from 4,000 to 6,000 metres; finally there is the hadal zone, from 6,000 to 11,000 metres.

- When sperm whales dive deep to hunt squid – using echolocation – they store oxygen in their muscles and blood, rather than in their lungs which collapse under the immense pressure, helped by their folding rib cages. The record for the deepest-diving mammal is the Cuvier’s beaked whale which, in 2014, was reported to descend to just shy of 3,000 metres, off the coast of Southern California.

- Come the 20th century, even after kerosene replaced whale oil as a fuel for domestic lighting, whales were still hunted aggressively for their oil which was used as in industrial lubricant, transmission fluid in cars, lipsticks, glues, crayons and margarine. In the 20th century alone, hunters killed 2.9 million whales.

- Dead whale carcasses fall to the seafloor, providing vital food to deep-sea species. “Separate courses are eaten by distinct groups of dining companions among the hundreds of species that take their turn at the banquet,” Scales writes. First are the hagfish, sleeper sharks and crabs. Then snails, crabs and worms feed on the scraps. Finally, it’s the turn of bone-eating worms called osedax.

- In order to avoid predators hunting with bioluminescence, some deep-sea species of fish have evolved to have ultra-black skin. “The key to the fish skins’ extreme blackness is the size and arrangement of melanin granules,” writes Scales. “When photons of light fall on the skin, they bounce sideways between granules (like the ball ricocheting between flippers and bumpers inside a pinball machine) and essentially get trapped, with very little light escaping.”

- Dotted across the deep ocean floors are hydrothermal vent fields which teem with life. Venting fluids combine with dissolved minerals and metals to build spires and chimneys, some growing as fast as 30cms a day. One of the tallest, nicknamed Godzilla, was discovered in the Endeavour vent field, off the west coast of Canada, in the 1990s. It eventually grew to 45 metres in height before toppling over. It’s believed that living cells first emerged on our planet within these hydrothermal vents.

- There are shrimps living on certain hydrothermal vents which have evolved giant eyes on their backs, filled with a visual pigment called rhodopsin. Rather than forming normal images, they allow the shrimps to perceive the thermal radiation emanating from the vents in the form of a dim glow.

- In 2010 a new species of deep-sea crab with a very hirsute undercarriage was discovered. Scientists named it the Hoff crab after David Hasselhoff, the actor from TV series Baywatch with a hairy chest.

- Satellites in Earth’s orbit can precisely measure the height of underwater mountains, or seamounts, by locating slight bulges in the seawater above them. “Seamounts can be so big and dense they exert a gravitational pull on the seawater around them… in the same way the Moon tugs at the oceans,” Scales writes.

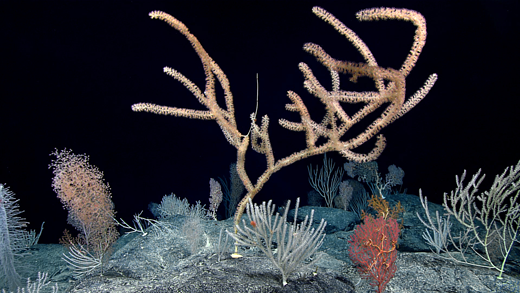

- The oldest animals on seamounts are black corals which are believed to have started growing around 4,200 years ago.

- Seawater circulates around the planet, driven by temperature and salinity, in a process known as the global conveyor belt. “It takes on average 1,000 years for individual water molecules to complete a single loop of the conveyor belt,” Scales writes. “The ocean takes deep breaths, constantly inhaling and slowly exhaling over decades and centuries, mixing its contents and in the process not just regulating heat but also distributing nutrients, oxygen and carbon throughout the ocean.”

- Slow-moving deep-sea animals have evolved an armoury of unusual chemical weapons to make themselves inedible to predators. Already chemicals from sponges, crinoids, fungi and bacteria have been proven effective in the treatment of breast cancer, malaria, ovarian cancer, leukemia and HIV.

- The fishing industry is keen to exploit an abundant species living in the twilight zone called lanternfish for use as animal feed and omega-3 supplements. However, deep-dwelling fish capture and store vast amounts of carbon dioxide.

- In the past, governments regularly used to dump lethal chemical weapons at sea. It’s estimated that around a million tonnes have been sunk, “all of them a long way out of sight”.

- Mining companies are making plans to exploit the seabed for rocky nodules and seamounts which contain valuable metals such as nickel, copper, cobalt and gold.

“In April 2021, several companies sent ships to the central Pacific to conduct surveys before they hope to be given the green light for their deep-sea mines,” Scales tells Chart magazine. Members of a United Nations organisation called the International Seabed Authority can buy permits for mining exploration of the sea floor. The authority has not yet granted permission for actual mining but Scales fears it soon will.

The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed by Helen Scales is published by Bloomsbury Sigma. Photo:Helen Scales

Yellow sponge. Image credit: NOAA

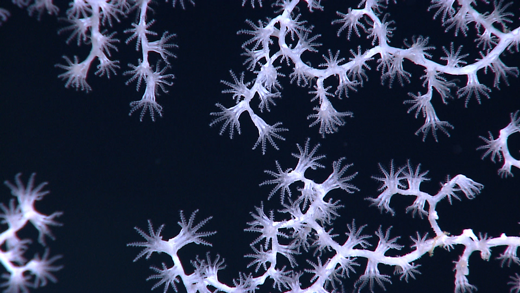

Octocoral polyps. Image Credit: NOAA

Forest of the Wierd. Image Credit: NOAA

Coral and squat lobster. Image credit: NOAA

Corals on seamount. Image credit: NOAA

Dumbo octopus. Image credit: NOAA

Giant yellow bamboo coral. Image credit: NOAA

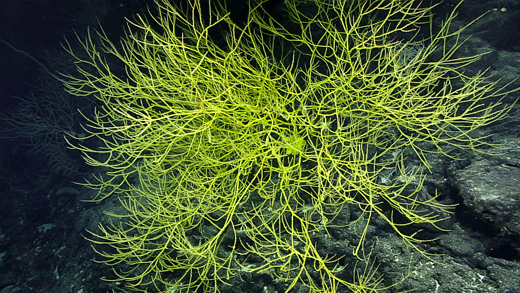

Iridogorgia coral. Image credit: NOAA

Banner image - Crossota Jellyfish Image credit: NOAA