Fishing methods are accidentally killing albatrosses all across the world’s oceans. Now a team of environmentalists are on a mission to save them.

Image credit: Fer-nando. Unsplash

Image credit: Fer-nando. Unsplash

Albatrosses need our help. No less than 15 of the 22 albatross species found in the wild are now threatened with extinction due to accidental capture in commercial fishing (known as bycatch). Since the 1990s, some species’ populations have halved. Without conservation efforts, these remarkable sea birds could be lost forever.

Fortunately the birds have an important ally in the Albatross Task Force. This international team of experts, led by two charities (the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and BirdLife International), is on a mission to reduce bycatch by 80 per cent in some of the deadliest fishing areas for albatrosses.

By helping governments implement regulations, and by showing fishing crews simple ways to stop killing sea birds, the task force has achieved eye-catching results. One example is in the hake fisheries off the coast of Namibia, where albatross deaths have been reduced by 98 per cent: the equivalent of 22,000 birds saved every year since 2015.

Rory Crawford is manager at the Albatross Task Force. He explains to Chart magazine how albatrosses are more vulnerable to commercial fishing than many other species. “Albatrosses mainly feed on squid and fish on the surface of the water, so foraging for bait or discarded fish around fishing vessels mirrors their natural behaviour,” he says.

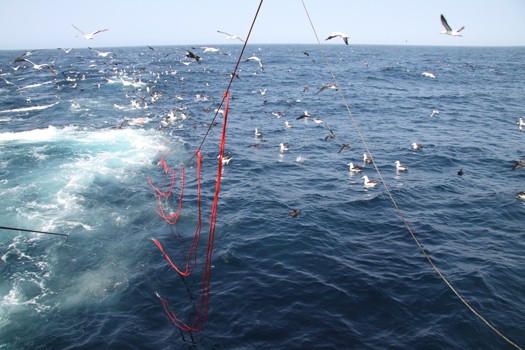

The problem is particularly bad around factory boats – the large trawlers that process the fish as soon as they’re caught. “The heads and guts are tossed over the side, which attracts scavenging birds,” Crawford adds. “They can smell this free meal from 20kms away. There can be hundreds of albatrosses diving in a feeding frenzy. The huge steel cables that pull the trawl net can easily snap a bird’s wing – and an albatross with a bust wing is good for nothing.”

Longline fishing poses problem too. For this, boat crews use baited hooks to catch larger surface species such as tuna and swordfish, as well as sea-floor species like cod, halibut and haddock. The albatrosses dive to catch the bait as it is fed out from the stern of the boats into the water. They might snatch a few morsels, but if their beaks snag on a hook, entire birds can be pulled underwater and drowned.

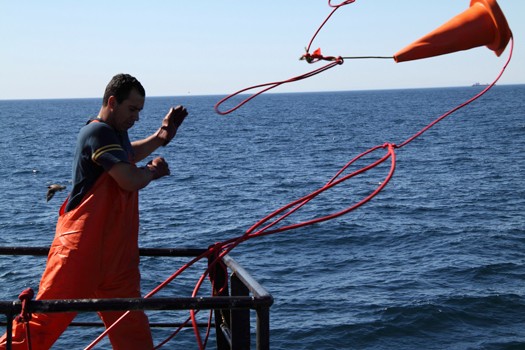

Normal longline fishing lines take time to sink to the optimal fishing depth. Crawford encourages fishing crews to save sea birds by adapting their methods slightly: weighting the lines ensures they sink quickly beyond the birds’ reach; colourful streamers can be used to scare the birds away from hooks or cables; and night-time fishing reduces sea bird bycatch since few species forage in the dark. “These measures are actually quite simple and don’t adversely impact the weight of catch,” Crawford adds.

Albatrosses are awe-inspiring birds. The smaller species have wingspans of around 1.8 metres, while the largest – the wandering albatross, for example, which has the widest wingspan of any bird on Earth – can reach beyond 3.5 metres. The birds are generally long-living too, thought to reach 70 to 80 years old, although no extensive records exist. The oldest known wild bird is a Laysan albatross called Wisdom, who is still laying eggs on Midway Atoll, in the North Pacific, at the ripe old age of 69.

Crawford explains how breeding pairs return to their birthplace to start families of their own, and typically mate for life. Should one partner die, though, the widowed bird rarely seeks out another mate. Therefore, every time a young breeding bird is killed as a result of fishing bycatch, dozens of future chicks will never be born.

In maritime mythology, the harming or killing of albatrosses is considered disastrous luck. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, the famous poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, has cemented this superstition. Crawford believes there is a stronger bind between humans and albatrosses, though.

“There’s a human connection around loyalty and partnership, and their resolute investment in young. Albatross behaviours and life patterns are surprisingly similar to our own. I think that’s why people relate so strongly to them.”

He also stresses how important it is that conservationists should explain to people who rely on commercial fishing what the effects of their industry on wildlife can be. “At the end of the day, conservation is about people more than the habitats or species we care about,” he says. “We’re dealing with anthropogenic threats. The key ingredient for an albatross task force instructor is therefore their ability to engage with people and not be dogmatic. We have to see the situation from both sides.

“If you’re looking out from the back of a trawler and there’s hundreds of yellow-nosed albatrosses around the vessel, you'd have a job being convinced that it’s a threatened bird. So, we show the fishermen pictures of the birds’ mid-Atlantic breeding grounds in 1970 compared to the same sites today. The fishermen respect the majesty of an albatross and are often ready to help.”

It’s not all softly, softly, though. The Albatross Task Force works closely with governments to introduce new regulations and gain access to boats as observers. “The legislation needs to have sharp teeth or it won’t bite,” Crawford warns. “But you also need flexibility on board to understand the pressures faced by fishermen.”

Inevitably, some fishing crews struggle to understand why albatross conservation is so important. “The albatross is a symbol of hope and freedom,” Crawford says in answer to this. “It’s such an international species, flying across national borders and entire oceans, which aren’t owned by anyone. Therefore, albatross conservation speaks to the need for collaborative international efforts. A black-browed albatross might nest on the Falklands, then fly up through Argentina, Uruguay and into southern Brazil – so all those countries need to be involved. It’s a bird that brings nations together.”

Crawford remains optimistic about his task. His team’s success in Namibia, for example, fills him with hope. “I live for results like Namibia. In just five years, thousands and thousands of marine birds have not been killed, due to some really quite simple steps. That’s amazing, don’t you think?”

Sam and Titus from ATF on freezer trawler. Image credit: Albatross Task Force

Atlantic yellow nosed albatross courting display. Image credit: Ben Dilley

Image credit: RSPB

Bird-scaring lines in Namibia

Image Credit: John Paterson, Namibia fishery images

Image Credit: RSPB

Banner image: White chinned petrel.

Credit Alistair-J-King - Namibia fishery images