In the third of a series of articles on the systemic risk of modelling, we look at confirmation bias, and the impact it can have on underwriters’ decision-making.

Did you know that 864 people were killed on commercial airline flights in 2014? If you’re afraid of flying, that’s a shocking death toll.

In 2015 there were 471 fatalities.

Last year it was 271.

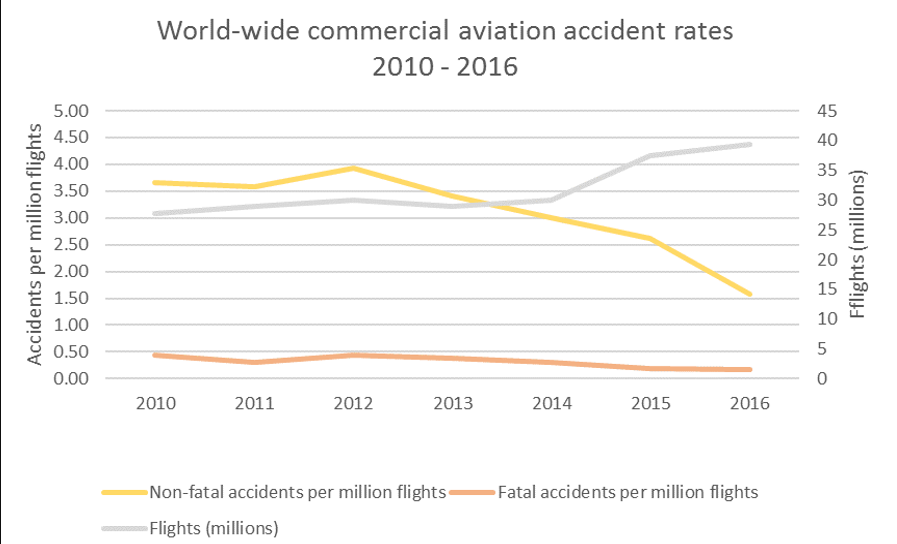

If you look at the chart below you can see evidence that flying is getting safer. Or at least that the number of people killed in air crashes in the last three years is getting smaller.

According to aviation consultants to70, fatal accidents in 2016 occurred in just one in every five million flights.

Pretty convincing evidence. But if you’re afraid of flying, it’s unlikely any of this will change your mind.

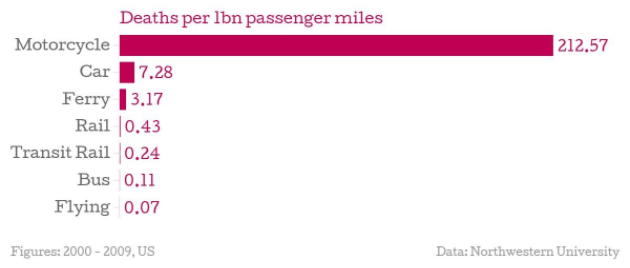

Still not convinced? How about the chart below from department of economics at Northwestern University?

A ‘slam dunk’ for aviation as the safest mode of transport. Irrefutable evidence that you’re safer on a plane than a motorbike.

But if you’re afraid of flying none of this is likely to help you get over your fear.

That’s because rather than weighing up the evidence – which in terms of aviation safety is pretty overwhelming – fearful flyers may seek out information that confirms their anxieties, rather than look at evidence that contradicts what they believe to be true.

In other words, some fearful flyers actually look for and read stories about plane crashes which just reinforces their view that flying is dangerous.

In psychology this is known as confirmation bias.

So what has this got to do with insurance underwriting?

Well (re)insurers use sophisticated but imperfect models and data sets to estimate risk. And MS Amlin is leading the way in trying to better understand the role models play in the insurance sector and their potential impact on the insurance market as a whole.

Is the industry too reliant on modelling?

Are those using the models aware of cognitive traits, such as confirmation bias, when making their decisions on risk?

Modern underwriting uses a combination of computer modelling and human skills. So it’s important to understand how our brains process information and how that might impact on decisions.

Confirmation bias can come into play when underwriters check their models for errors. Sometimes this can lead to ‘biased error’ searches of models and data sets. In other words, those checking the models are looking for expected errors that confirm their existing view, rather than looking for unexpected errors in the models. Confirmation bias predicts that underwriters will prioritise the information from models that confirms their beliefs and expectations and will tend to downplay information that suggests a contrary view would be more appropriate. As the use of models increases and the number of models potentially reduces, it is vital that the insurance business understands how confirmation bias may be influencing underwriting decisions.

The effect of cognitive bias on decision making is a human trait that has occupied Oxford academic Anders Sandberg and his colleagues for some time now. He is part of a working party set up by MS Amlin to look at the potential impact of modelling on the stability and future success of the global insurance market.

Anders is a neuroscientist and has spent the last three years trying to understand the complex relationship between underwriters and the computer models we use to make decisions.

“When you talk to people who work in insurance and underwriting in particular it’s fascinating to watch how the information flows,” said Anders.

“And when you are dealing with big disasters, catastrophic events, you are relying on a combination of data, knowledge and human experience. So understanding the way underwriters reach their decisions is crucial.”

The challenge for Anders and the rest of the team is pinpointing the types of cognitive bias, and what if any effect it had on their decisions.

It is this kind of detail that is important when trying to understand the potential impact of over-reliance on modelling.

“One of the biggest conundrums is that regulators demand that insurers use modelling to make their decisions,” says Anders.

“But this subtly means that insurers are drawn more and more towards modelling.

“Regulators want markets that work well and that they can survive the normal business cycles. So a deeper understanding of how underwriters reach their decisions is crucial.”

It’s an example of how important it is to understand the relationship between the computerised models and those who use them to make multi-million pound decisions about risk.

At stake here is the long-term future of a sustainable, effective insurance market that can survive the ups and downs of financial cycles. The lessons from the 2008 financial crash highlighted the systemic risk of modelling and was a factor in MS Amlin’s decision to promote scientific research into the subject.

And in our next article we will look at another kind of bias, known as ‘The Autopilot Problem’. And it is a challenge that goes to the heart of the whole issue surrounding the use of modelling and the impact it could have on insurance markets as a whole.