This is where old aeroplanes go to die. These aircraft junkyards in the Californian desert are the subject of a new book by Californian photographer Troy Paiva.

There are thousands of old aeroplanes parked in the deserts of the American Southwest. After years of service in the military or for commercial airlines, they have been unceremoniously dumped in junkyards and left to die. It’s an ignoble end for these beautiful flying machines.

But there is one man trying to give them dignity in their afterlives. Troy Paiva is a San Francisco-based photographer who specialises in shooting old vehicles, buildings and machinery. His latest book, Boneyard: SoCal’s Aircraft Graveyards at Night, brings together his intriguing photos from the aircraft junkyards of Southern California.

“The whole idea is to show the fallibility and finite nature of all these machines we make,” Troy explains. “The more we take them for granted, the more interesting they are. I’m fascinated by technology and machines in general: decommissioned military bases, junkyards of every description, bypassed and abandoned roadside towns, derelict amusement parks, industrial infrastructure, hospitals, hotels, ocean liners… But aeroplanes are one of my favourites. I’m a geek for this stuff.”

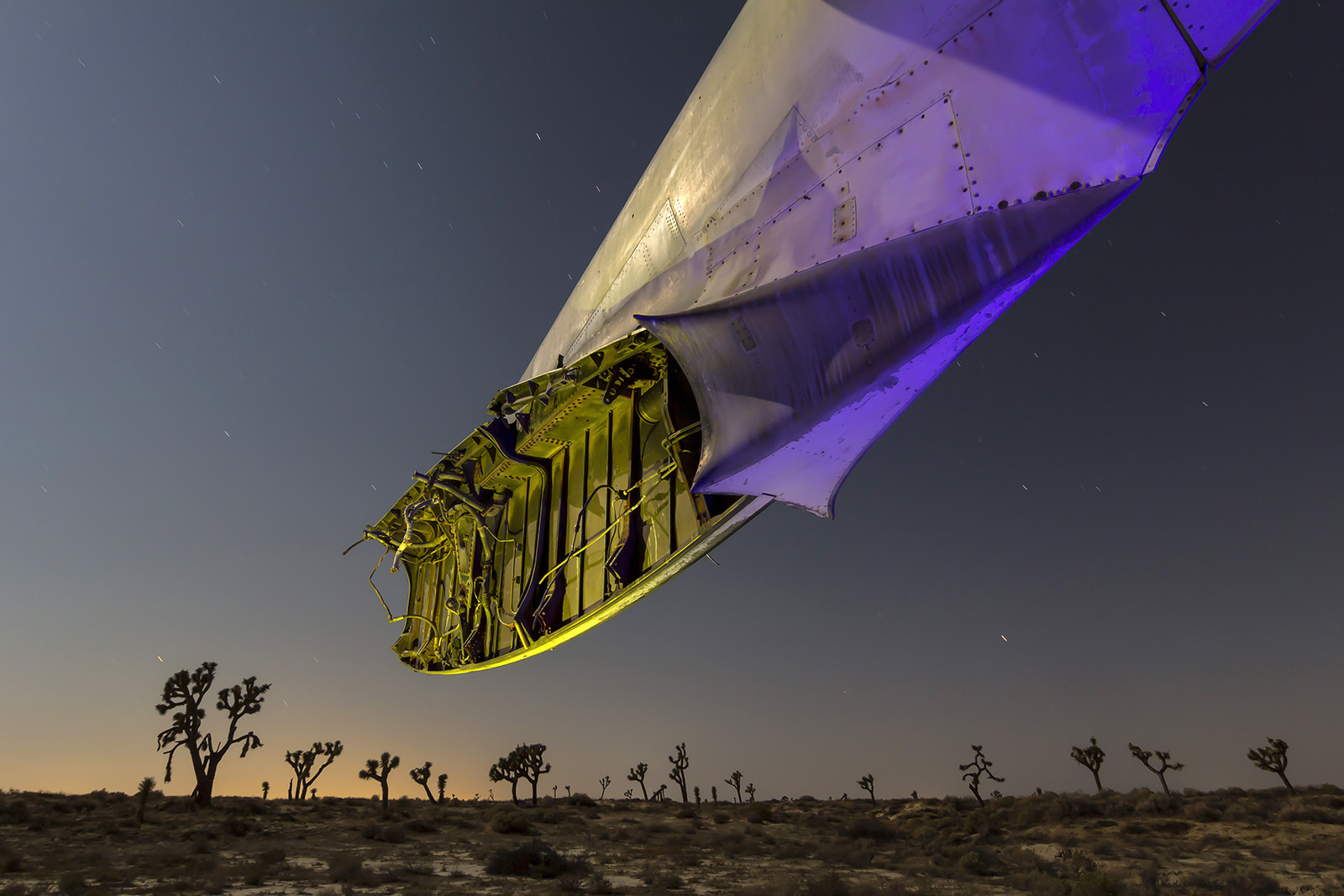

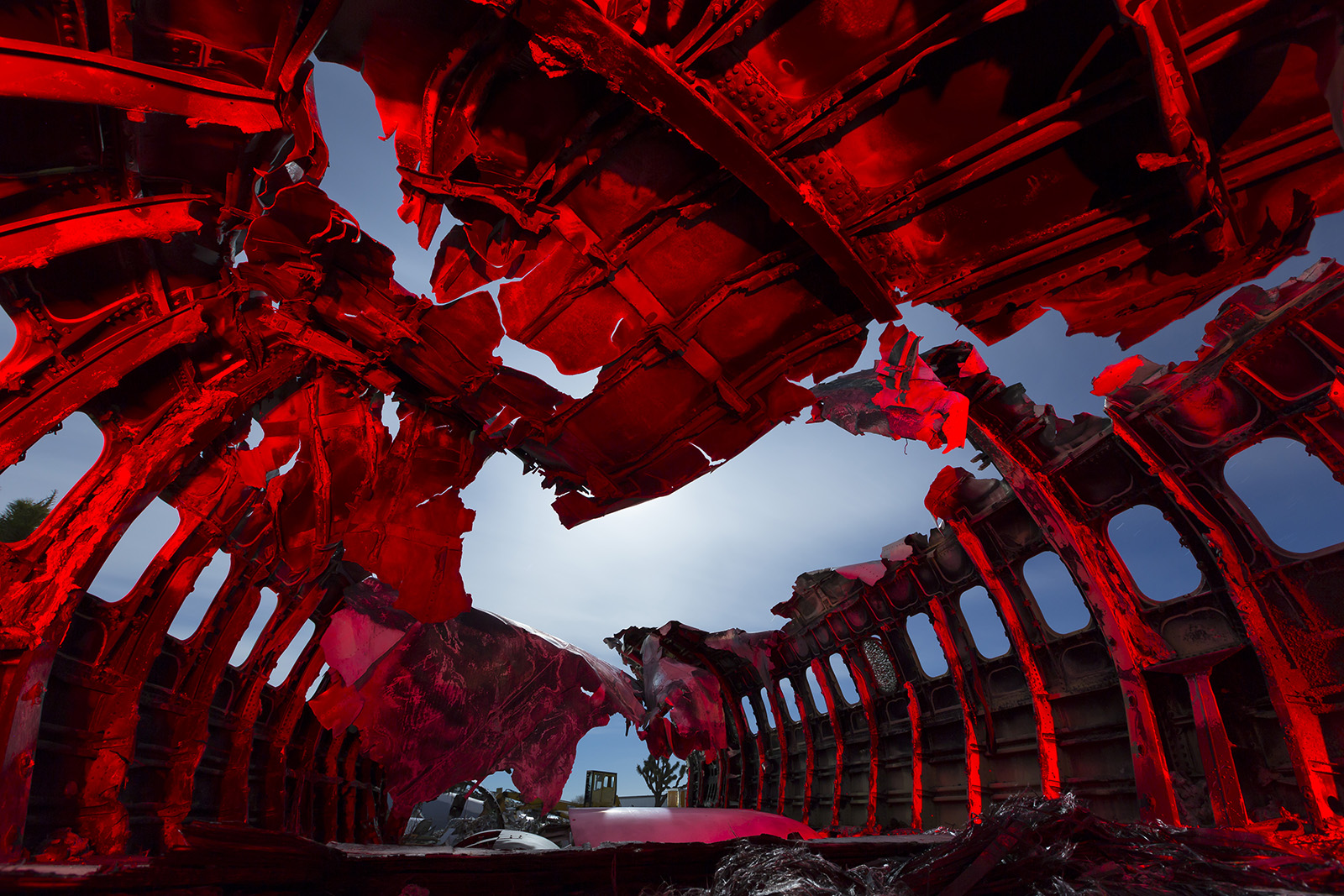

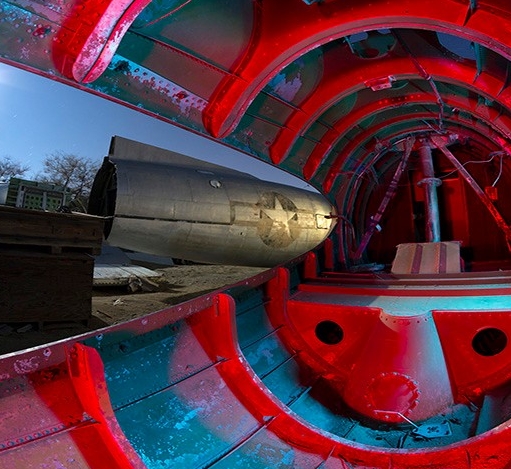

Troy is slightly unorthodox in that he photographs only at night-time, illuminating his subjects with the full moon or hand-held strobes and electric torches. It imbues his images with a surreal, almost ghostly quality.

In this latest book, his models include a whole smorgasbord of aircraft languishing in junkyards in the Mojave Desert.

There are jet fighters, bombers, passenger jets, airliners, cargo aircraft, business jets, light aircraft, even a handful of helicopters. Manufacturers include Boeing, Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas, North American Aviation, Northrop, Convair, Fairchild Hiller, Learjet and Cessna.

Most have been cannibalised of all their reusable parts, as if their bones have been picked by vultures. Others look closer to their original working state but have still deteriorated in the desert climate. All are ghosts of their former selves, brought back to life through this arresting photography. “Angels of the Mojave,” Troy calls them.