In advance of summer 2021, when meteorologists warned of killer heat waves in North America, northern states such as Washington, Oregon and British Columbia were surely far off their radar. But not now. In June, a heat dome settled over the Pacific Northwest, bringing temperatures that burnt a mark in the history books and caused extreme misery for humans, animals, the infrastructure and the environment.

The Oregon city of Portland registered 46 degrees Celsius, a temperature deemed extreme in Sudan or Saudi Arabia. The all-time state record was broken by nine degrees. In Washington State, Seattle nudged 42 degrees Celsius. Lytton, a small village in British Columbia, set a new high for Canada, maxing out at 49.4 degrees Celsius, before a wildfire gutted the homes of its 250 residents.

Hundreds in the Pacific Northwest were reported to have died in what officials described as a mass casualty event. There were 78 tragic deaths from overheating in Washington State – double the total over the last five years. Public venues such as libraries opened their doors as cooling centres for sweltering citizens. Many of the casualties were found living alone without the comfort of air conditioning.

“This huge jump in mortality due to heat is tragic and something many people thought they’d never see in the Pacific Northwest, with its mostly moderate climate,” said Dr Scott Lindquist, Washington’s state health officer. “But climates are changing, and we see the evidence of that with dramatic weather events, major flooding, historic forest fires, and more.”

Infrastructure in the region was also heavily affected, adding to the apocalyptic feel. The extreme heat warped Seattle’s highways and scorched Portland’s streetcar wires, suspending services. A major power company brought in rolling power outages for the first time in its history, in response to a strain on the system caused by high demand, as residents ran their air conditioners and fans at top capacity.

Maritime massacre

Environmentalists estimated that more than one billion sea creatures along the Vancouver coast were cooked to death, demonstrating the unnatural spike in temperatures. Close to Vancouver Island, as many as a million mussels died in an area the size of a tennis court, while 100 million barnacles were baked in a one-kilometre zone. They fear the destruction of these keystone shellfish could threaten many other ocean species such as starfish, crabs and birds that thrive in the filtered coastal water.

“Eventually, parts of the British Columbia coast may become more like Hong Kong and other hot parts of the world where many of the intertidal species die off every single summer,” cautioned Christopher Harley, a professor at the University of British Columbia, who surveyed the catastrophe for biodiversity.

As the temperatures fell, the questions continued to mount up. Was climate change to blame? Was this a freakish blip or a grim portent of things to come?

Blocks of weather

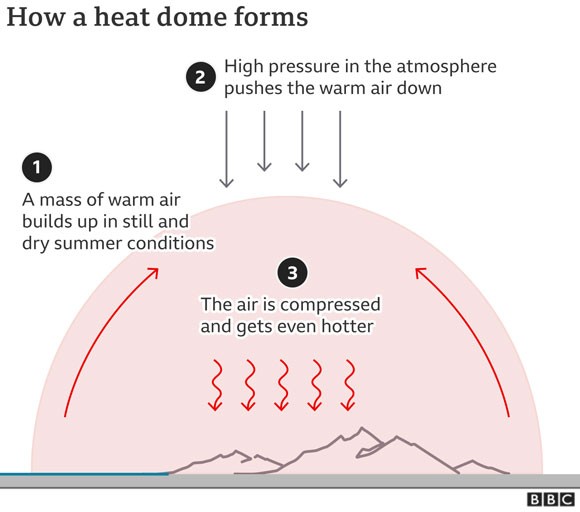

Andrew Hoell, a drought expert with the US government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, explained how heat domes are caused. “Our weather is largely governed by what’s called atmospheric blocking,” he told Chart magazine. “The weather marches across the planet in blocks, heavily influenced by the jet stream. If the jet stream breaks apart or slows down, then the blocks pile up on each other, as they lose momentum. Imagine a marching band or line of lemmings crashing to a halt.”

The atmosphere traps hot air like a lid or cap. This hot air sinks down to the ground and bakes the earth below through compression. Eventually the blocks start moving again and the cap is released.

Climate scientists have quickly pointed the finger at fossil fuels as the cause of the heat domes. The phenomenon was “virtually impossible without human-caused climate change,” according to analysis by an international group of climate scientists called the World Weather Attribution. “As warming continues, it will become a lot less rare,” the study warned.

Hoell was more cautious, however, about making a direct link between heat domes and melting ice caps or greenhouse gases. “There’s a temptation to blame everything on global warming, and the media are quick to report on it,” he said. “Others say it’s related to [the weather phenomena] El Niño or La Niña, heating or cooling the North Pacific. Science has too many grey areas, with too much room for bias in the models. We’ve observed atmospheric circulations and blocks, which lead to heat domes, for as long as we’ve observed the weather and the climate. We need to work out how climate change affects the atmospheric circulation and therefore the prevalence of these blocks, both in terms of how often they form and how long they last. Science owes it to society to find those answers because, at the moment, we’re just not sure.”

Rain dance

Hoell certainly falls into the “freakish blip” school of thought for the Pacific Northwest heat dome in June. “It was just so far off the charts,” he adds. “There’s no baseline to compare it with. This was a once-in-a-500-year or millennium event. 30-degree-Celsius heat waves? Sure, every year. But I don’t expect to see a spike like this in the next 50 years.”

Not that he is ready to relax. “The West [of North America] is enduring a period of low precipitation, compounded by a background climate rise of 1 to 2 degrees Celsius. We haven’t had the rain or snowfall during the winter. Any precipitation is sucked up by the parched soil before it can reach the reservoirs. Water resources have plummeted as a result. The impact of higher temperatures, such as heat domes, can become very hazardous downstream.”

But what can be done to avoid extreme heat in the future? “People in the US aren’t going to stop burning greenhouse gases anytime soon,” Hoell conceded. “Climate change is here to stay. That’s the reality. We wouldn’t even be talking about this if it were raining and snowing.”

There’s no need to panic… yet. “Better rains will return,” Hoell predicts. “But what happens when the West [of North America] goes through another dry period later in the century, when temperatures are even higher? We’re unlikely to face a water crisis in my lifetime. In my children’s? Yes, that’s a real cause for concern. People might start to favour regions with reliable precipitation, rather than beautiful weather. If you don't have the water, what are you going to do?”

How a heat dome forms Image source: BBC

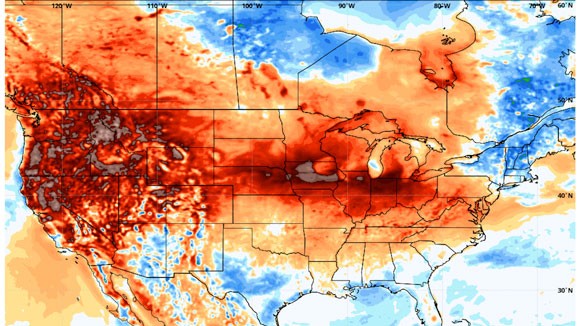

Unprecedented heat wave in Pacific Northwest.

Image by Hans Reniers. Credit:Unsplash

Computer model projection for temperature departures from average.

(Image credit WeatherBell.com)

Image by Patrick Perkins. Image credit: Unsplash

Image by Ava Sol. Image credit: Unsplash

Banner image by Patrick Perkins. Image credit: Unsplash