Meet the marine scientist who has devoted his career to locating sunken shipwrecks. Here he explains the trials and tribulations of his very unusual job.

Image credit: NOAA. Unsplash

Image credit: NOAA. Unsplash

"Searching for shipwrecks is an all-or-nothing proposition, where you either find what you are looking for or go home empty-handed. The risks and rewards are great and so are the emotions that you go through as a result. I have experienced searing disappointment when a search ends in failure. Fortunately, I have also known the unbridled joy that success brings.”

This is David Mearns describing the highs and lows of searching for shipwrecks at the bottom of the ocean. For the last 30 years this marine scientist and oceanographer has scoured the world’s oceans for famous, and occasionally infamous, sunken wrecks. When there are suspicions about a ship’s demise, it's insurance companies or criminal investigators who hire his services. More recently, though, he has been employed by the relatives of mariners or passengers who perished when the ships sank. Head of a Sussex-based company called Blue Water Recoveries, he says he has located 25 or so major undersea wrecks – 90 per cent of those he has set out to seek.

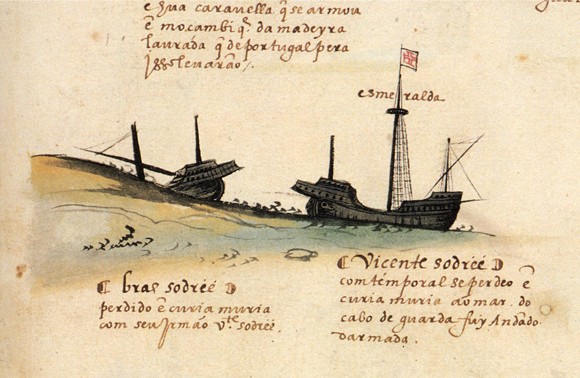

Over the last three decades, discoveries include HMS Hood, the Royal Navy battlecruiser sunk by the German battleship Bismarck; HMAS Sydney and HSK Kormoran, opponent warships in a World War II sea battle off the coast of Western Australia; MV Derbyshire, a British bulk carrier lost in 1980 during a Pacific typhoon; AHS Centaur, a World War II hospital ship sunk by a Japanese submarine off the coast of Queensland; Esmeralda, a Portuguese carrack that came to rest off the coast of Oman in 1503; and MV Lucona, a motor vessel sabotaged with a time bomb as part of an insurance fraud.

Mearns also locates sunken aircraft. In 2011, he helped pinpoint the final resting place of Air France Flight 447, which had crashed in the Atlantic Ocean two years previously. And in 2019 he found the light aircraft which tragically crashed into the English Channel with Argentinean footballer Emiliano Sala aboard.

Mearns’ methods require an unusual mixture of skills. Charged with locating a particular shipwreck, he first spends many long hours in libraries and archives, poring over old maritime records and eye-witness reports from rescuers and survivors. While searching for HMAS Sydney and HSK Kormoran, for example, he decoded a book that a German captain had used while in prison to secretly document the original sea battle. “The stuff of World War II movies like The Great Escape,” is how Mearns describes that discovery.

He also analyses weather reports, and records of the positions, speeds and bearings of the ships prior to sinking. One process he uses is called reverse drift analysis, where reports of wreck debris or life-rafts, for example, help him ascertain where the ship actually slipped beneath the waves.

But this is just the start. Once Mearns has identified a reasonable search area, he must then mobilise a team of marine specialists, and hire search boats and equipment.

The tools of his trade are inevitably rather specialised. As his boat cruises up and down the search zone, devices called side-scan sonars and multi-beam echo sounders are normally towed behind on the end of long cables. They emit acoustics which bounce back from the seabed, allowing Mearns to build up a computer image of the underwater terrain and, hopefully, any shipwreck or debris lying on it. When he finally pinpoints a wreck, he then uses a remotely-operated underwater vehicle (ROV) to film it or recover items.

With so much featureless ocean to search, it often requires weeks, even months, of painstaking and queasy work at sea. Sea legs and bags of patience are essential. For HMS Hood, Mearns had 630 square nautical miles to cover, for example; for HMAS Sydney it was over 1,750 square miles. Very occasionally, though, luck might serve up a lost shipwreck in just a few days.

Working with complicated, expensive machinery, out on the open ocean, is never a simple task. In his autobiography, The Shipwreck Hunter: A Lifetime of Extraordinary Deep-sea Discoveries, Mearns describes the potential problems: “The main culprits are rough weather and equipment failure. But over the course of my career I’ve had projects stopped dead in their tracks for a host of other unexpected reasons, including ships breaking down or catching fire, injuries to personnel requiring helicopter medevac, loss of sonar [equipment] and ROVs, and in one instance literally running out of food, prompting an urgent return to port.”

He swears all the effort and time at sea are worth it, though, especially when relatives of the sailors lost at sea are desperate to learn the fate and final resting place of their loved ones.

“The moment you find a wreck is exhilarating,” he says. “There’s a lot of adrenalin involved. It’s like winning a gold medal: you spend years training for it and working on it, and it’s achieved in a second when you cross that winning tape; when you see the shipwreck pop up on your sonar screen.”

One of Mearns’s current projects could prove to be the most exciting yet of his entire career. Last year he joined a campaign team hoping to locate the wreck of HMT Empire Windrush, the famous passenger liner that in 1948 brought the first cohort of post-World War II Caribbean migrants to the UK – the spearhead of the so-called Windrush generation. In 1954, en route from Japan to the UK, the ship caught fire and sank in the Mediterranean, off the coast of Algeria. Apart from four engineers who were killed, the rest of the crew and all the passengers escaped.

Mearns and his team have narrowed down a search area for the wreck of the Empire Windrush – 23 nautical miles off the coast of Algeria, 2,800 metres deep. They now want to raise the ship’s stern anchor, bring it home to the UK, and display it “as a memorial to post-World War II British multiculturalism”. But it’s going to be a very costly operation. They are raising funds through gofundme.com.

Mearns believes the recovered anchor would be a powerful emblem. “As the centrepiece of a monument somewhere in the UK, it will become a touchstone for people to visit and connect themselves to that ship and the symbolism of it.”

www.gofundme.com/f/monument-for-the-windrush-generation

Image: David Mearns

HMAS Sydney. Image credit : WA Museum and Curtin University.

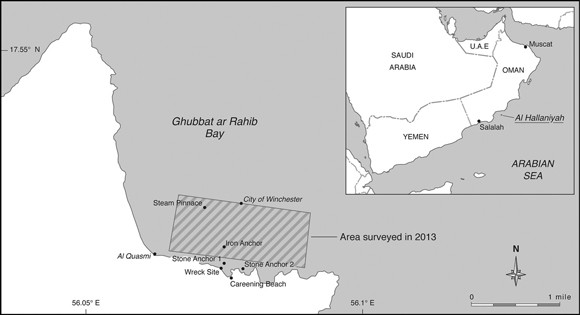

Location of the wreck‐site and other cultural heritage material discovered within Ghubbat ar Rahib Bay (T. Cousins, P Holt).

Illustration from the Livro das Armadas dá India, c.1568, depicting the loss of Brás and Vicente Sodré's ships. The name below the Portuguese cross identifies Vicente's ship as the Esmeralda (Image credit: Academia das Ciências de Lisboa).

David Mearn's book

HMT Empire Windrush. Image Credit: Windrush Foundation

HMS hood Bell rim detail.

Image Credit: The National Museum of the Royal Navy

Banner image: Divers excavate the wreck site of Vasco da Gama's ship the Esmeralda.

Image credit: Blue Water Recoveries via AP