Glenn Schneider has witnessed 35 total solar eclipses in his lifetime. What drives this American astronomer to travel the world in pursuit of darkness?

Siberia, the Zambezi River, Java, the Aleutian Islands, China’s Hubei province, Easter Island, the Arctic and the Antarctic… Glenn Schneider certainly likes to get off the beaten track. When he heads off abroad, though, it’s a mission he’s on rather than a holiday. This American astronomer travels the world in pursuit of total solar eclipses. He is what they call in the industry an umbraphile, or shadow-lover.

So far, since his very first one, as a 14-year-old schoolboy in 1970, he has clocked up an impressive 35 eclipses in all. Along with two other Americans, he shares the world record for the greatest number viewed.

A total solar eclipse can only occur when the Sun, Moon and Earth align (in what’s known as syzygy), so that the Moon (if close enough to the Earth) completely blocks out the bright light of the Sun, allowing just the faint solar corona to be visible. It’s rare, occurring somewhere on the planet only every 16 months or so.

Totality – the central phase when the Moon obscures the entire disk of the Sun, and casts observers into darkness – lasts just a few minutes. During all of Glenn’s 35 total solar eclipses, he has spent just one hour and 51 minutes altogether observing totality.

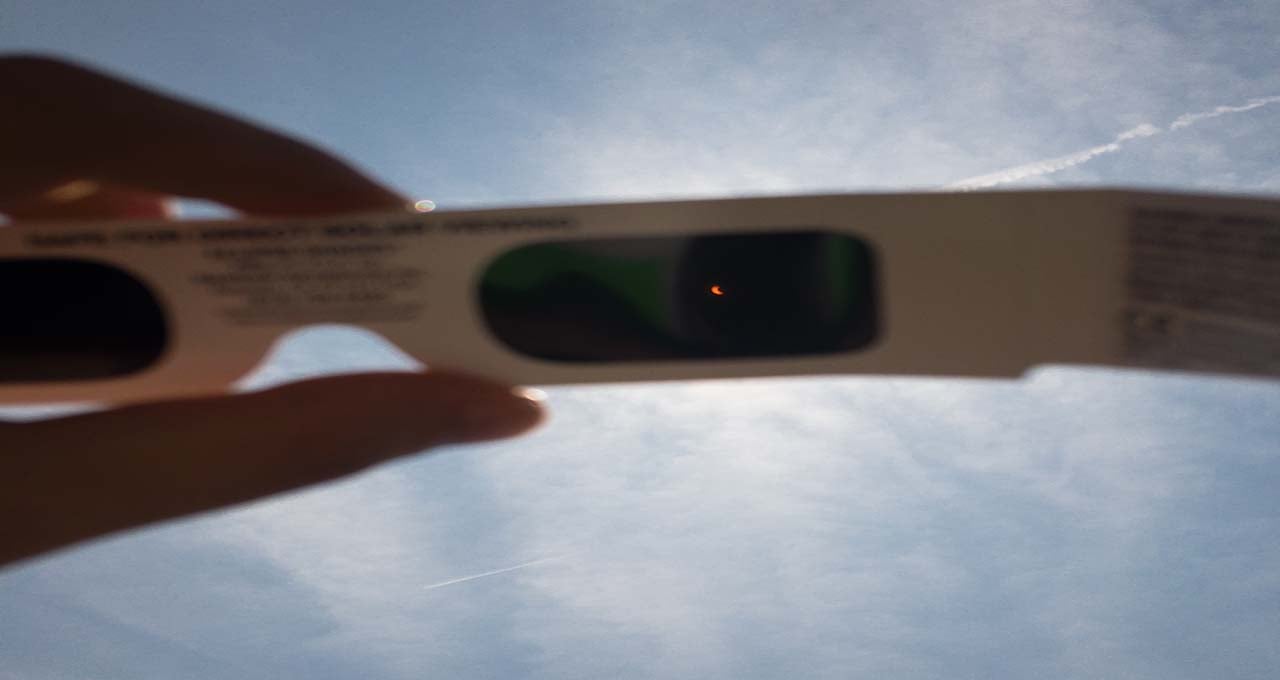

He swears it’s all worth the effort and global travel, though. Anyone who has experienced a total eclipse will know what a thrilling, emotional phenomenon it can be: the beauty of the corona, the diamond ring effect, Baily’s beads (when the light shines through the valleys on the Moon’s surface), and the way the lunar shadow rolls in rapidly from the west, imposing night-time in the middle of the day.

The air temperature drops, the wind changes, birds and other wildlife become visibly confused. First-time human observers never really know how they’re going to react to this cosmic spectacle: some are stunned into silence, some cheer, some scream, some even burst into tears.

“You really feel your place in the universe,” Glenn explains. “It's a connection to celestial mechanics in a very visceral way. It connects the scale of human experience to celestial experience.”

It’s thanks to a beautiful astronomical coincidence that we are able to experience total solar eclipses at all. The Sun’s diameter is 400 times the Moon’s, and the Sun is, on average, 400 times further away than the Moon. This makes both bodies appear the same size in the sky, so that, in a total solar eclipse, the Moon blocks out the Sun perfectly.

Image credit: Patrick Schneider, Unsplash

Glenn explains that it’s an equally beautiful coincidence that there are sentient beings around to witness eclipses. Every year, the Moon’s orbit draws away from the Earth by a few centimetres so that, millions of years from now, it will be too far away to occlude the Sun. Right now, in the Earth’s 4.5 billion-year history, cosmic conditions are perfect.

As a professional astronomer, Glenn has spent much of his life observing the heavens, but nothing, he says, is as rewarding as these eclipses. “It’s amazing, that sense of personal involvement you get when you see totality, and the dynamics of the solar system in motion. It ties into people’s base emotions.”

After he lost his eclipse virginity in 1970, Glenn became instantly hooked. “I’d read about eclipses and understood the phenomenology, but I didn't understand how overwhelming it would be,” he remembers.

A New York City schoolboy at the time, he travelled down to North Carolina to catch the moment, armed with cameras, telescope and binoculars. He knew totality would last just two minutes and 40 seconds, so for several weeks beforehand he had planned and rehearsed meticulously how he was going to spectate and capture precious images.

Image credit: Scott Szarapka, Unsplash

“As the Moon’s shadow approached, and just before totality, I was thunderstruck. It was the most incredible thing I’d ever seen: a wall of darkness coming across and enveloping us; a very high-contrast umbra; the advent of second contact and the diamond ring. It was all unbelievable.”

For Glenn, the experience was almost spiritual. “I stood there with my binoculars dangling around my neck, looking at that hole in the sky. I couldn't move. I didn't take a single photo. I was mesmerised. It froze me right to the spot, and changed my perception of what I was going to do with the rest of my life.”

Indeed, Glenn became an astronomer by profession. He now works in Tucson, Arizona, at the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory. Although his particular field is the search for exoplanets, not solar eclipses, there is a strong connection.

Unfortunately though, his university doesn't fund his eclipse-chasing addiction. He pays for almost all of it himself. “It’s my one vice,” he says. “I don't drink. I don't smoke. I don't gamble. I drive a Kia Rio. I don't spend income on the usual vices. I find inexpensive ways to travel.”

Occasionally he might earn a free trip on an observation aircraft by using his astronomical knowledge to plan logistics and flight paths for other umbraphiles. This was the case in July 2019 when he joined a group on board a Boeing 787-9 Dreamliner that took off from Easter Island, in the southeastern Pacific, and flew north to intercept the path of the eclipse at an altitude where cloud cover poses no problems, and at a speed which artificially increased the duration of totality to around nine minutes. Naturally, everyone got a window seat.

Even after 35 eclipses, Glenn’s zeal hasn’t faded in the slightest. “Every eclipse is different,” he explains. “There is so much difference in appearance and phenomena. It never gets old. It amazes me that people can see one and then go for decades without seeing another.”

One of his most memorable experiences was in 2002, in the Australian outback, when he located himself at the very end of the path of totality, where the darkness lifted up into the sky rather than across the surface of the Earth. “We looked straight up and saw this elongated oval of darkness getting smaller and smaller, lifting back up into space,” he remembers. “It was one of the most amazing things I’ve ever seen.”

More recently, in 2013, he travelled with a group to northern Kenya, to the remote region around Lake Turkana. Preparing themselves for totality, they noticed a “biblical sandstorm” coming in to spoil the party. Desperate not to miss the eclipse, they all jumped aboard their chartered aeroplane and persuaded the pilot to fly them above the storm for a perfect view.

Glenn has at least a further three eclipses penned in his diary. In December 2020 he will be in northern Patagonia, in Argentina. The following year he’ll be observing from an aeroplane either above Antarctica or the Southern Ocean. And 2023 will see him in northwestern Australia. “All of my vacation time is allocated for the rest of my life,” he says.

In 60 years’ time an eclipse will cross over Glenn’s home city of New York. “If I survive to 123 years old, I’d love to see that one,” he says. “Eclipses keep me young.”

Even so, he’s realistic about his prospects. “That’s the year 2079. Unfortunately, I don’t think I’ll make that one. But my daughter will be 85 years old, and she has instructions on exactly where to go to see it.”

Umbraphilia, it seems, runs in the family.

Over the next ten years, seven total solar eclipses will occur.

- December 14, 2020: Chile, Argentina and Polynesia

- December 4, 2021: Antarctica

- April 8, 2024: Mexico, USA and Canada

- August 12, 2026: Arctic, Greenland, Iceland, Spain and Portugal

- August 2, 2027: Spain, North Africa, Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Somalia

- July 22, 2028: Australia and New Zealand

- November 25, 2030: Botswana, South Africa, Australia

- Image credit: Jongsun Lee, Unsplash null

- Image credit: Jim Strasma, Unsplash null

- Image credit: Yong Chuan Tan, Unsplash null

- Image credit: Melanie Dretvic null