The shipping industry must eventually abandon fossil fuels. Here is one venture leading the charge in hydrogen power.

Just as there are more and more hydrogen-powered motor-cars on our roads, it won’t be long before there are similarly powered ships cruising our oceans.

The technology required is growing fast. Two leaders in the field are Swiss-Swedish technology company ASEA Brown Boveri (ABB) and French hydrogen energy specialists HDF Energy. In April 2020 they agreed to start jointly manufacturing hydrogen fuel cells on a grand scale – from a new factory in Bordeaux – with a view to selling the technology to shipping companies all over the world.

ABB initially expects short-distance shipping companies to use the fuel cells, sometimes cruising completely on hydrogen fuel-cell power, and at other times switching to a hybrid of fuel-cell power and battery power.

Ferry companies, which typically operate across short expanses of water, are already interested in this hybrid system of propulsion. Norwegian shipyard Fiskerstrand is a good example. Based on an island called Sula, off Norway’s coast, it has been exploring the possibility of running ferries through the country’s fjords. Along with ABB, it has teamed up with a research facility in Trondheim called SINTEF.

Also in Scandinavia, there is a Finnish research vessel called Aranda, which is testing ABB’s new hybrid technology. When performing experiments, research vessels normally switch off their main engines to eliminate interference from noise, vibrations and air pollution. Hydrogen fuel cells allow the Aranda to continue powering its equipment without running its engines.

Another pioneering project is Flagships, which will see hydrogen fuel-cell vessels powering both a ferry service near the Norwegian city of Stavanger and a pusher tug in the French city of Lyon, on the River Rhone.

Jostein Bogen is in charge of energy storage and fuel cells in ABB’s marine and ports division. “It is only a matter of time before the many advantages of fuel-cell technology are within the grasp of the entire maritime sector,” he told Chart magazine. “We also see this feasible for deep-sea shipping, at least as an auxiliary power source.”

Jostein Bogen, who is in charge of energy storage and fuel cells in the marine and ports division at Swiss-Swedish technology firm, ASEA Brown Boveri (ABB).

He claims the systems have advanced significantly over the last decade, and that by 2023 the energy driving ships will be measured in megawatts, rather than a few hundred kilowatts, as it currently is.

“The technology is responsive enough to be used as a general energy source for most loads on electric ships, and can be deployed in combination with other systems,” he adds. “For example, vessels that operate predominantly on diesel engines could employ fuel cells to boost efficiency and comply with regulations in areas such as fjords and zero-emission ports.”

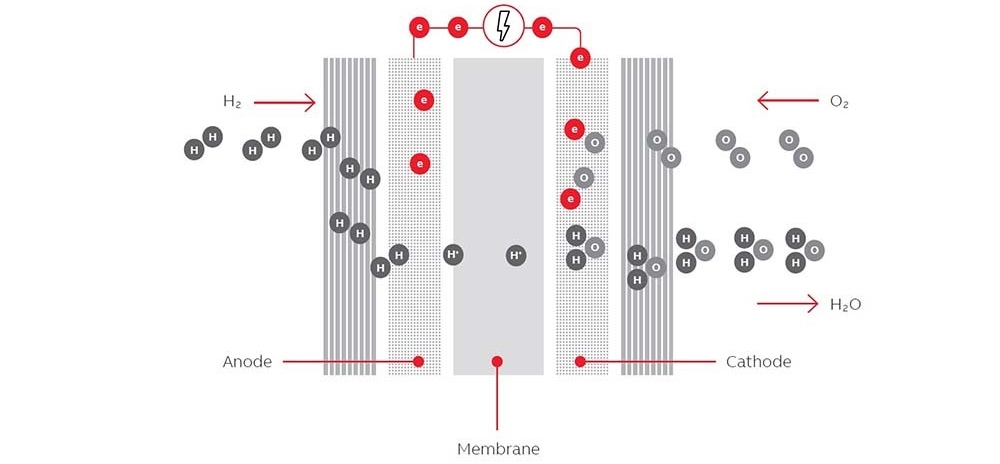

So how exactly do these hydrogen fuel cells work? The technical name for the system that ABB and HDF Energy are developing is ‘proton exchange membrane fuel cells’. Each cell consists of two electrodes, separated by a polymer membrane electrolyte, and coated with a platinum catalyst layer. Together this forms what’s called a membrane electrode assembly.

Once the hydrogen fuel is fed in, the catalyst at the negative electrode separates molecules into protons and electrons, the latter passing through an external circuit, thereby creating a flow of electricity. Individual fuel cells combine in a fuel-cell stack to produce enough electricity to power a ship. Crucially, there is no combustion – just a direct conversion of fuel into electricity, with heat and water as by-products.

“With the use of renewables to produce the hydrogen, the entire energy chain can be clean,” Bogen insists.

ABB has teamed up with a Canadian manufacturer called Ballard Power Systems to develop these fuel-cell power systems. In February 2020, Ballard’s director of advanced manufacturing, Dr Lee Sweetland, explained how, in recent years, the speed with which membrane electrode assemblies (the core component of fuel cells) are manufactured has accelerated exponentially, reducing the overall production costs by a huge amount.

“When I first started in the fuel-cell industry, membrane electrode assemblies were produced by hand, using discrete printing technologies and a tremendous amount of labour,” he said. “As volumes have increased, Ballard has moved on to continuous processes.”

He claimed his company would soon be able to produce a finished membrane electrode assembly “in just five seconds”. “This is seven times faster than our current production rate,” he added.

But that’s all in the future. First of all, hydrogen fuel-cell propulsion must prove itself on short-distance sea routes.

A fuel-cell stack, used to produce energy.

The pusher tugs on the River Rhone are a good place to start. ABB will provide the power, enabling the tug to shuttle barges along the urban section of the river. Much of its work will involve transporting barges filled with refuse collected from across the city. When it comes to refuelling the pusher tugs, the plan is for removeable fuel tanks to be refilled with hydrogen created at an electrolysis plant powered by energy from the Rhone’s hydroelectric dams.

Victor Laravoire, who works for transport group Sogestran, and is overseeing the project, envisages a “virtuous circle” of energy transmission.

“The great river’s water flow will create the energy, which will create the hydrogen, which then is used on a barge on the river,” he says. “On the barge, the water formed in the fuel-cell reaction to create power is then returned to the river as the by-product from the fuel cell.”

Initial tests on the pusher tug are due to take place in April 2021.

Back at ABB, Bogen is upbeat about the future of hydrogen-powered ships. “Fuel cells are being produced at a larger scale, their cost is coming down, and they are becoming more compact,” he says. “This is a technology that is progressing rapidly, and it will soon be helping the industry as a whole to meet its targets for carbon dioxide reduction.”