Wonder Woman, unexploded ordnance, porpoises, shipwrecks… all in a day’s work for the hydrographers on the mighty River Thames, as Colin Hubbuck discovers.

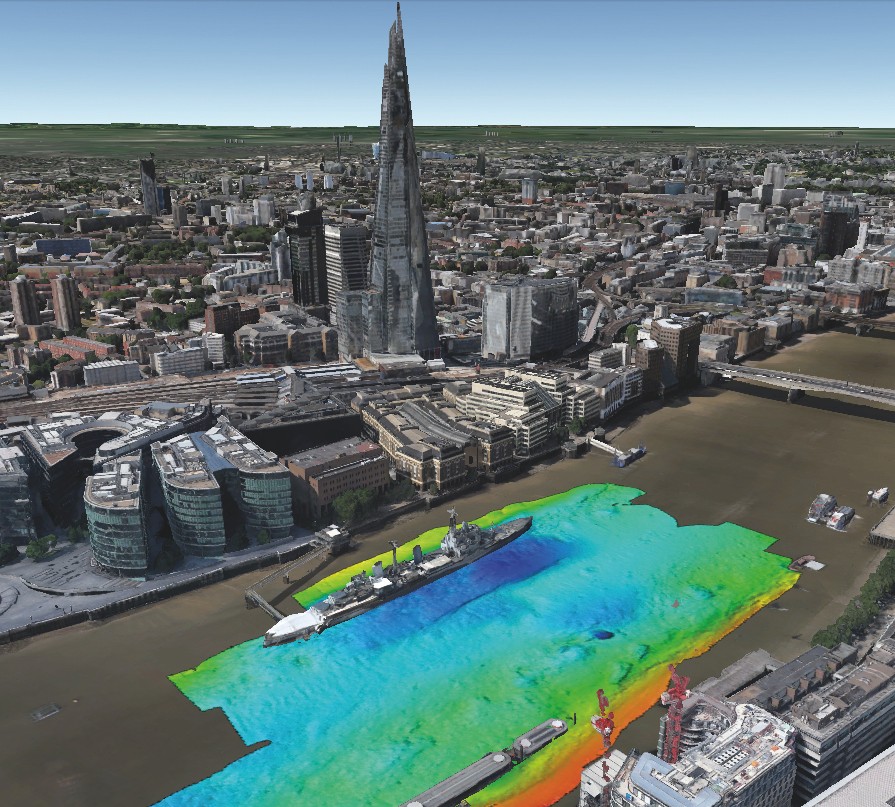

Down on the riverbed, at the bottom of the Thames, it’s so dark and murky that divers struggle to see their hands in front of their faces. No such problems for the hydrographers working for the Port of London Authority. Their data-gathering equipment is so high-tech that they claim they can identify items on the riverbed only 12cm long. Just as well since it’s their job to ensure the entire London stretch of the Thames – 400 square miles in all, from Teddington in the west to the North Sea in the east – is safe for river traffic.

And sometimes that traffic can be very large indeed. Like the 400-metre-long container ship, the Al Muraykh, which has docked at London Gateway (the capital’s container terminal) with over 18,000 containers on board. This ocean-going behemoth wouldn’t have found its way up the shipping channel without the maps and navigational information provided by the PLA surveyors. It’s fair to call them the unsung heroes of London’s shipping industry.

Jim Powell is senior surveyor at the PLA. On board one of his team’s five vessels, the Maplin, on a recent trip to survey the edges of the shipping channel close to London Gateway, he explained the challenges he faces. “The river is constantly changing. It doesn’t stand still. We get regular users up in the shallow end (as they call the western end of the tidal Thames) who say: ‘We think we touched the bottom here’. So we’ll go and have a look. When there were the floods a few years ago, all the sand shoals that we knew were there suddenly disappeared. Where did they move to? We had to investigate.”

Part of Powell’s role is to produce 3D images of underwater infrastructure; calculating the volume of material that needs to be removed prior to a dredging or demolition operation, for example. They inspect walls, weirs and power station pipes. Often commercial companies will have old plans of their buildings which the surveyors can update and correct. If need be, they can pinpoint the best spot to drop a diver, saving time and cost.

Passing a colony of seals sunning themselves on the sandbank, Powell extols the virtues of his job. “Working on boats is a bit addictive, even in rough weather. We work right up in central London with a lot of traffic, or right out in the estuary where you can’t see land. You see harbour porpoises, seals, loads of cormorants. You never get tired of sights like that.”

Above: One of the Port of London Authority's scans of the Thames riverbed.