When construction is finally completed, the Jeddah Tower in Saudi Arabia will be the world’s tallest building, at over 1,000 metres. How much higher can skyscrapers soar?

Image credit: Jeddah Economic Company

Image credit: Jeddah Economic Company

They promise it will rise to more than a thousand metres into the sky, making it the world’s tallest building by quite a margin. Right now, though, Jeddah Tower stands at barely 250 metres, and the workers have downed tools because of labour disputes and the arrest of senior staff during the 2017 Saudi Arabian purge.

Provided construction restarts, this 167-storey superstructure will eventually scrape the sky above a new city called Jeddah Economic City, just north of Jeddah, on Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Coast. By breaking the record for the world’s tallest building, the developers say they hope to aggrandise the international image of both Jeddah and Saudi Arabia as a whole.

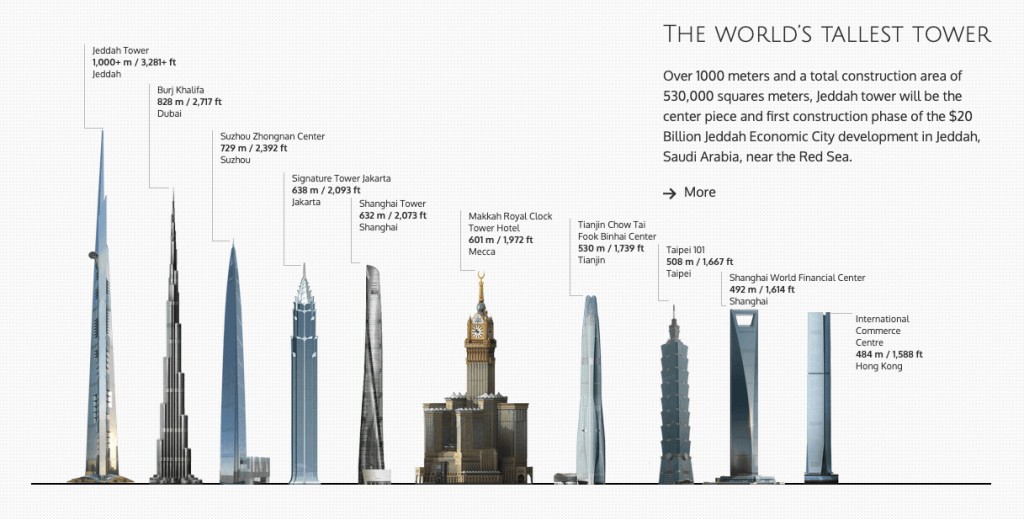

This planet of ours is bristling with super-tall buildings, all doing their utmost to draw attention to the cities they rise out of. Right now, the tallest of all is Burj Khalifa, in Dubai, at 828 metres. Below that, there are nine other buildings taller than 500 metres – five in China, and one each in Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, South Korea and the United States.

As feats of engineering – like rockets reaching for the heavens – they are certainly impressive. But why such an obsession with being the tallest? Does size really matter?

Daniel Safarik is editor-in-chief at the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, in Chicago, an organisation that researches skyscrapers, and officially ranks buildings by height. He believes humans will continue to construct taller and taller buildings, possibly as high as 2,000 metres.

“There is a consensus among engineers that a 2,000-metre, or approximately mile-high skyscraper is achievable by today’s technology,” he tells Chart magazine. “But whether this would be financially practical is another matter.”

Safarik pinpoints the main purposes for these giants of architecture. “In the traditional North American central business district, with expensive real estate and the need to house a large headquarters, there is a strong economic argument for making the most of that block of space, by stacking as high as possible,” he says. “One is also making a statement of power and prestige.”

In a desert environment – as is the case with Jeddah Tower – space is not at a premium. “In the middle of a desert, one is almost exclusively making a statement about power and prestige,” Safarik adds.

The other benefit of enormous skyscrapers, he says, is that the technology they engender aids the construction industry as a whole. “Faster elevators, better anti-swaying devices, advanced mechanical systems, solar glare-resistant glass etc… the learnings from shooting for the moon can come to benefit those of us who must make do with run-of-the-mill 40-storey towers in our daily lives.”

Even in a post-pandemic world where so many office-workers are now working from home, Safarik believes there will still be an appetite for skyscrapers. “Although there may be less of a desire to fill them with cheek-by-jowl co-working spaces,” he adds. “If we can work out the spacing of people in elevators, then we may see a good many high-rises with lower population densities overall. Hopefully it will also mean more cut-outs, outdoor spaces, and other ways to get fresh air – a trend that was already underway.”

Constructing skyscrapers is nothing new. It all started in 1885 with Chicago’s (now demolished) 10-storey, 42 metre-high Home Insurance Building – the first time a steel frame was used to support the entire weight of the building, rather than normal load-bearing masonry. Developers in Chicago, New York City and London soon embarked on what can only be described as a sky race. Unshackled by strict planning regulations, it was New York which took the lead. In 1930, the Bank of Manhattan Trust Building (now 40 Wall Street), at 283 metres, held the record for being the world’s tallest, quickly followed by the Chrysler Building (319 metres) and then the Empire State Building (381 metres), which kept the record for the next 40 years.

From then on, skyscraper after skyscraper appeared on metropolis skylines around the world. Cities grew bigger and land became more expensive, while the technology of steel framing, fireproofing, concrete, passenger lifts and glass improved exponentially.

In 1972 the North Tower of the World Trade Center in New York took the record at 417 metres, swiftly followed by the Sears Tower in Chicago (442 metres). Then the sky race moved to Asia – with Malaysia’s 452-metre Petronas Towers and Taiwan’s 509-metre Taipei 101 – before Dubai’s Burj Khalifa trumped the lot with its 828 metres.

Both the Burj Khalifa and the future Jeddah Tower have Y-shaped cross-sections with three wings emerging from a triangular core. The architects of Jeddah Tower are a company called Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture. (Smith also designed the Burj Khalifa.)

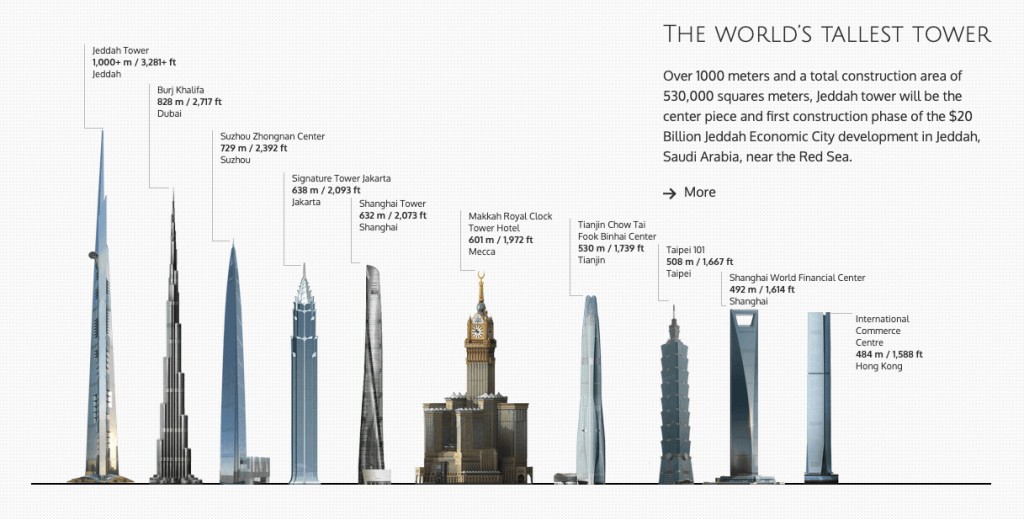

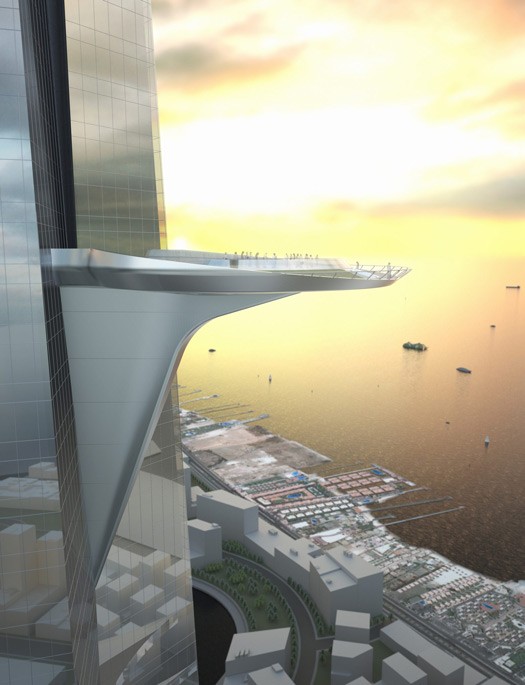

They explain how their new design features 59 elevators serving the building, some of them double-decked. The elevators to the observatory will ascend and descend at 10 metres per second. The tapering wings of the building are intended to be aerodynamic, so that the whole structure won’t oscillate in the wind. The architects have also designed notches in all three sides of the tower to “create pockets of shadow that shield areas of the building from the sun and provide outdoor terraces with stunning views”. The entire tower is expected to have a final cost of $1.2 billion.

Of course they need to build it first. When that will be is not clear. Chart magazine approached the architects, the developers (Jeddah Economic Company), and the parent company (Kingdom Holding Company). All three declined to respond.

Even Safarik at the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat is somewhat in the dark. “The official word is that Jeddah Tower is ‘under construction’,” he says. “But I’m afraid we have not gotten an update in quite a while.”

Image credit: Jeddah Economic Company

Image credit: Jeddah Economic Company

Image credit: Jeddah Economic Company

Image credit: Jeddah Economic Company

Banner image credit: Getty