A new report from the United Nations warns of the risk of catastrophic dam failure in countries all over the world as infrastructure deteriorates with age.

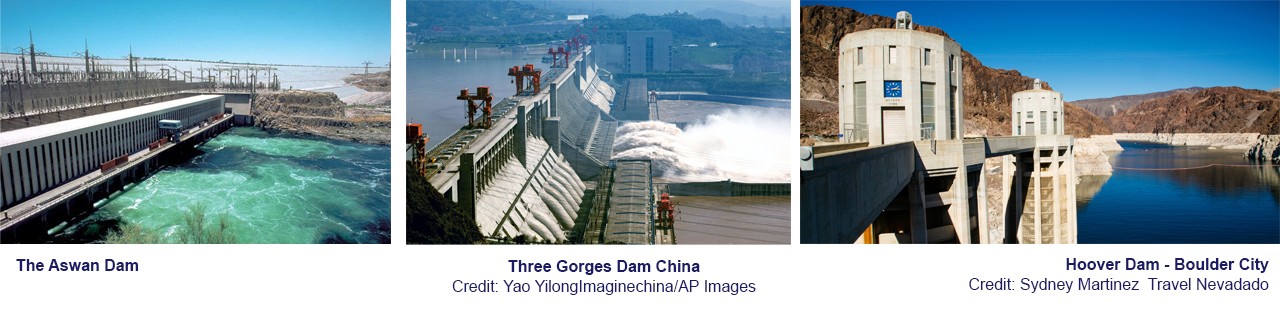

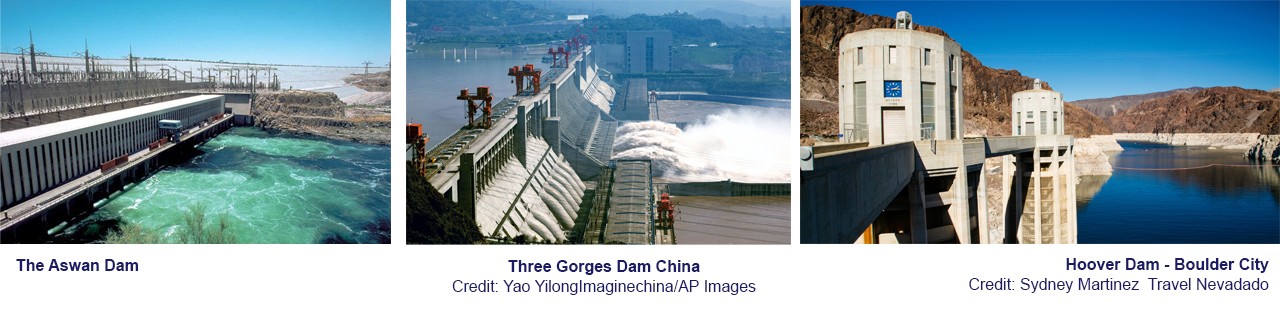

The world’s most famous dams – the Aswan (in Egypt), for example, or the Three Gorges (in China), or the Hoover (in the United States) – are all symbols of national pride. Until they fail, that is.

In 1975, China’s Banqiao Dam collapsed during Typhoon Nina. As 61 other Chinese dams were destroyed in the ensuing disaster, the overall death toll is believed to have reached 220,000. But Maoist China suppressed the news, and the world only learnt about the catastrophe in 1990. A national symbol became an international embarrassment.

It was poor construction that caused the Banqiao catastrophe. However, if a dam barely 20 years old could fail, how much graver is the risk posed by dams of the same generation that are now approaching 70 years old?

Ageing dams are the focus of a new report from the United Nations University Institute on Water, Environment and Health. Entitled Ageing Water Storage Infrastructure: An Emerging Global Risk, it warns of the global risk “as tens of thousands of existing large dams have reached or exceeded an ‘alert’ age threshold of 50 years, and many others will soon approach 100 years”.

The threat from old dams increases as the rate of new construction diminishes. Many of the best locations have been exploited: nearly 50 per cent of global river volume is fragmented or regulated by dams. Large dam use is questioned on social and environmental grounds: alternative methods of water-storage and energy production methods mean their heyday has passed.

The risk of failure, meanwhile, remains, whether from seepage, cracking, over-topping or collapse. In recent years, dam failures have generated headlines, from Zambia’s Kandesha Dam, and the UK’s Toddbrook Reservoir, to Edenville Dam in the US state of Michigan. On the whole, incidents such as these result in evacuations and local misery. But, how close are we to another catastrophe on the scale of Banqiao?

The UN report dwells on the 125-year-old Mullaperiyar Dam in the Indian state of Kerala, downstream of which live 3.5 million, increasingly nervous people. “Mullaperiyar is an example of an old, large dam, which has been debated on political and technical grounds for its continuous functioning in a seismically active area amidst structural flaws, political stresses and environmental issues,” says Dr Duminda Perera, one of the report’s authors. Deforestation, landslides, increased rainfall and the risk of earthquakes make it vulnerable. The role it played in devastating flooding in 2018 is a matter of political dispute. However, calls to decommission the dam are growing louder.

Decommissioning is complicated, time-consuming and expensive, affecting a country’s culture, economy and energy supply. It is accelerating in the USA and Europe, less so in other parts of the world where the cost can prove prohibitive. The report says managing the decommissioning process must be a “global goal”.

Retreating behind national boundaries is insufficient. After all, the Mullaperiyar Dam was built by the British at the height of their colonial rule of India, part of a contract that granted them access to resources and minerals they were quick to exploit. So where does responsibility for the dam now lie, as the sound of its creaking increases?

As the report concludes: “Overall, dam decommissioning should be seen as equally important as dam building in the overall planning process on water storage infrastructure.”

USA & Canada

Asia & Pacific

Europe

Africa

Water released by Sanmenxia Dam on August 28, 2019 in Sanmenxia, Henan Province of China. (Image credit: Visual China Group / Getty)

Kariba Dam in Africa

(Image credit: Jekesai Njikizana / AFP / Getty)

Helicopter drops sandbags onto the dam wall at Toddbrook reservoir

(Image credit: Leon Neal/Getty)

Mullaperiyar dam

3.5 million people are at risk if India's Mullaperiyar Dam fails.

Banner image credit: Kees-Streefkerk / unsplash