The crew manifest of Ernest Shackleton’s ill-fated ship Endurance – which headed for Antarctica in 1914 – listed the names of 27 men, including the captain. There were, however, 28 men aboard. When the ship had docked at Buenos Aires, en route to Antarctica, a stowaway named Perce Blackborow, desperate for employment and more than a little adventure, had sneaked aboard.

Shackleton was enraged when he discovered Blackborow’s deceit, and berated him in front of the crew. “If we run out of food and anyone has to be eaten, you will be first! Do you understand?” he bellowed at the youngster.

The reply he received was this: “They’d get a lot more meat off you, sir.” Blackborow was lucky his cheekiness appealed to Shackleton’s sense of humour. Instead of being thrown overboard, he was put to work in the ship’s galley.

Stowaways have existed for as long as human beings have been sailing boats across the seas. Some do it to escape their old lives, or to gain free passage, or in a bid for asylum. Others are simply seeking adventure.

Over the centuries there have been some incredible tales of maritime hitchhikers. One of the first to be documented was that of a Spanish explorer called Vasco Núñez de Balboa. In the early 1500s, while living on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, he fell into serious debt and fled his creditors by hiding in a flour barrel – along with his pet dog – on a ship bound for Panama. From then on his fortunes changed, though. He eventually worked his way up to becoming governor of a new Central American colony, and was a key figure in the Spanish conquest of South America. Modern-day Panama even named its currency after him.

There is often a glamorous side to stowing away. During the early 20th Century – as newspaper reports and Hollywood movies romanticised world travel – a craze developed. According to Laurie Gwen Shapiro, author of The Stowaway: A Young Man’s Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica, the fad reached its peak in the late 1920s when more than 500 stowaways were arrested and deported from New York City’s Ellis Island.

“Many of these rapscallions were determined to see new worlds,” Shapiro wrote in The New Yorker magazine. “Such youngsters wanted a taste of the adventures they had glimpsed at the movies. And, in the new age of the mass media, each stowaway’s story of success incited more attempts.”

Often the risks reaped rewards. In 1928, a 20-year-old actress called Rose Host, keen to further her career in Hollywood, crept aboard a New York liner bound for California. Although she was forced to work for her passage, on arrival she waltzed straight into her first film role.

In the same year, a 19-year-old German called Johannes Thoening secured a free spot on board a ship from Hamburg to New York by getting accomplices to nail him and provisions inside a large box labelled ‘household goods’. He was discovered when dockworkers at his destination shifted his box so that he was upended on his head, forcing him to cry out. So impressed were New Yorkers by his ingenuity that he was quickly offered a job.

Few stowaway stories have such happy endings, though. Take the case of the Greenock stowaways. In 1868 six youngsters hid themselves aboard a ship in the Scottish port of Greenock that was bound for Canada. Once discovered, they were treated appallingly, regularly beaten and barely fed. Eventually, when the ship became trapped in sea ice off the coast of Newfoundland, six of them were forced overboard and told to walk across the ice to shore. Tragically, two died.

The captain and his first mate were eventually imprisoned for their cruelty. While their actions were criminal, their frustration at having so many illegal passengers aboard was perhaps understandable.

In modern times, stowaways are as much a problem as they ever were. Their acts cause huge inconvenience and expense, and occasionally end in disaster. Just look what happened in October 2020 when seven Nigerian stowaways triggered a military operation on an oil tanker off Britain’s south coast. Special forces soldiers stormed the vessel by helicopter after crew had reported threats and had hidden themselves inside the ship’s strong room.

The International Maritime Organization carries out global research on stowaway incidents. According to their 2017 figures (the latest they have), there were 432 incidents that year, involving 1,420 stowaways. The majority of them – over 250 – were Nigerian nationals. Other nationalities included around 175 Tanzanians, 150 Albanians, well over 100 Syrians, over 100 Moroccans and 70-odd Ghanaians. The two ports where most stowaways secreted themselves on ships were Durban in South Africa and Lagos in Nigeria. Other problem ports included Bilbao in Spain, Casablanca in Morocco and Douala in Cameroon. The estimated cost to the shipping industry in terms of delays, repatriation and safeguarding human life was US$9.5 million, which works out at $6,700 per stowaway.

The IMO defines a stowaway as “a person who is secreted on a ship, or in cargo which is subsequently loaded on the ship, without the consent of the ship owner or the master or any other responsible person”.

The organisation explains how modern-day stowaways are occasionally helped on board by port personnel, and how they typically hide in “empty containers, cargo holds, tanks, tunnels, behind false panels, stores, accommodation area, engine rooms, void spaces, cranes and chain lockers”.

But it emphasises how these illegal acts have serious consequences for the shipping industry as a whole. “The ship could be delayed in port; the repatriation of stowaways can be a very complex and costly procedure involving masters, shipowners, port authorities and agents; and the life of stowaways could be endangered as they may spend several days hidden, with the risk of suffocation and without any water or provisions.”

The IMO encourages ship crews to treat stowaways humanely and to respect asylum seekers. It urges ship masters to search ships thoroughly before embarking. But it also advocates that governments should prosecute stowaways.

Of course, the people who stow away have certain responsibilities, too, since they are the ones breaking the law. And, on being discovered, they’d be wise not to follow the example of Perce Blackborow on the Endurance. A cheeky answer back to the captain won't do them any favours.

The Endurance was slowly crushed after nine months trapped in the ice

Credit: Royal Geographical Society

Balboa carried on ship. Credit: www.gutenberg.org

Vasco Núñez de Balboa Credit: National Portrait Gallery

Rose Host

Oil tanker crew onboard Nave Andromeda 'called for help' after attempting to detain stowaways Credit: Andrew Matthews/PA Wire/PA Images

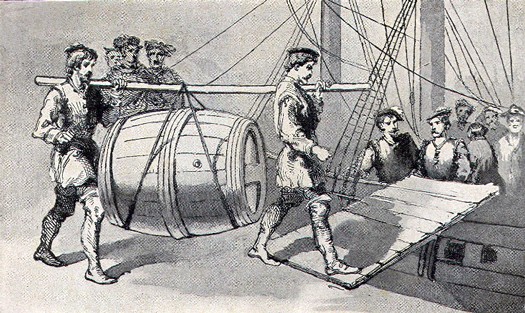

Banner image: Illustration from the London Evening News, 1850, of a ship's crew searching for stowaways prior to leaving harbour.