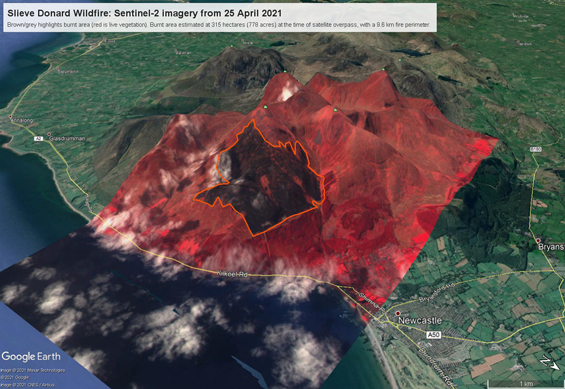

The summit of Slieve Donard, Northern Ireland’s highest mountain, is often hidden by cloud. In spring 2021, it was smoke rather than cloud, though, that shrouded the peak as a vast wildfire swept across the Mourne Mountains. For three days, dozens of firefighters battled the blaze – thought to be caused by arson – eventually bringing it under control.

Strong winds had fanned the flames across huge swathes of gorse and heather, devastating flora and fauna on one of Northern Ireland’s most famous landmarks. Over 100 firefighters, multiple vehicles and even aircraft (for observation) were deployed to extinguish the blaze which, at one point, was declared a major incident.

The National Trust, the conservation charity that owns part of the Mourne Mountains, said it was “devastated to see the impact the fire has had on the fragile habitat of upper Slieve Donard”. It added: “This area of outstanding natural beauty has been completely destroyed and will take years to recover.”

Compared to the vast infernos that regularly engulf parts of California and Australia, the Slieve Donard fire was a mere spark. Nevertheless, UK wildfires are becoming more common as global warming heats up. According to the European Forest Fire Information System (a European Commission body which monitors wildfires), there were 137 fires across areas larger than 30 hectares during 2019 (their latest figures).

A recent study from the University of Reading warns that climate change is going to exacerbate the problem over the next few decades as the UK experiences higher temperatures, stronger winds, and lower rainfall and humidity.

Climate scientist Professor Nigel Arnell led the research. “Extremely hot and dry conditions that are perfect for large wildfires are currently rare in the UK, but climate change will make them more and more common,” he warned. “In future decades, wildfires could pose as much of a threat to the UK as they currently do in the south of France or parts of Australia. This increased fire danger will threaten wildlife and the environment, as well as lives and property.”

Recent wildfire outbreaks on moorland and in forests across the British Isles support this research. Over the last few years, areas such as Saddleworth Moor in Greater Manchester, Winter Hill in Lancashire, Ilkley Moor in West Yorkshire, the Vale of Rheidol in Ceredigion, and the Ashdown Forest in Sussex have all been affected. In 2018 there was even a wildfire in the capital when Wanstead Flats, in northeast London, burnt out of control.

The worst incident in recent times, however, was on the Moray peninsula, up in the far north of Scotland, in the spring of 2019. This wildfire raged for over a fortnight. At its peak there were 80 firefighters, 19 fire engines and two helicopters in attendance. Before it was extinguished, it destroyed over 25 square miles (65 square kms) of peat and grassland.

There is no record of a British person dying in a countryside wildfire, in modern times at least. And British firefighters don't face anywhere close to the same risks as those toiling in California, Australia or certain Mediterranean nations. Nevertheless, as the world warms up and British summers become increasingly dry, they must plan for the future. Guillermo Rein is Professor of Fire Science at Imperial College London. “Wildfires are moving north,” he warns. “Northern France, Germany, Netherlands and Scandinavia are all seeing them. In a matter of years the UK will be ill prepared to handle wildfires. It must consider what it might need in the future, and learn from neighbours like France, Spain and Portugal.”

Planet Earth has been experiencing wildfires for the last 400 million years, ever since the Devonian period when land-based plants first evolved. Rather than disasters to be avoided at all costs, according to some scientists, fires are nature’s way of regulating oxygen levels in the atmosphere.

They can ignite for all sorts of reasons: volcanic activity, lightning, sparks from falling rocks, for example. More recently in Earth’s history, human beings have been the culprits. In the UK, humans are certainly the number one cause. This might be the result of camp fires, barbecues or bonfires; occasionally it’s catalytic converters on cars, or sparks from farm machinery; sometimes it’s prescribed burning that runs out of control; depressingly often – as suspected in the recent Slieve Donard fire – it’s arson that’s to blame. Surprisingly, cigarettes, which are made with fire-retardant paper, are not a major factor.

The majority of wildfires across the British Isles fall into four different categories: there are lowland heath fires, which often burn the heathland of southern England, for example; there are upland moor fires, such as Slieve Donard; there are grassland fires, and arable crop fires; finally there are the much rarer forest fires.

While the latter can be devastating in hotter regions, in the UK at least, they are usually easy to control since flames seldom jump between the crowns of trees. Back in 2011, however, there was an intense forest fire in Swinley Forest, in Berkshire, which blazed out of control, destroyed 165 hectares of forest, and forced residents to evacuate their homes.

It sounds counter-intuitive but heathland burns mainly in early spring when the moisture in heather is at its lowest. Grassland, on the other hand, burns in late summer when it’s driest and temperatures rise. Peat can burn at any time of year, provided the water table in the soil is low enough.

Typically, British fires are suppressed using water hoses and fire-beating tools. Other devices include back-mounted water sprayers and leaf blowers. The latter direct flames away from combustible vegetation. Water-carrying helicopters or aeroplanes are hardly ever used in the UK.

However, more important than reactive fire fighting is proactive land management. The Forestry Commission (the UK government department responsible for woodland management) advises landowners to create fire breaks within forests, and to clear plant debris on the ground. Prescribed, or controlled burning – a process where vegetation is cleared through burning – is another way to prevent widespread fires, but there are risks it can burn out of control.

Back at the University of Reading, researchers warn that “greater caution and more stringent guidelines” are needed when it comes to prescribed burning, especially in Scotland. (Here the practice is known as muirburn.)

The lead researcher, Professor Arnell, also advises UK authorities to bear in mind the risk of wildfires when granting planning permission for buildings. “This is particularly important at the rural-urban fringe and near heathland,” he told Chart magazine.

Additionally, he was concerned because British authorities base their fire planning on research from Canadian forests. “These are not necessarily ideal for UK wildfires, which are usually on heathland and moorland,” he added.

More disturbing, however, are his warnings that wildfires will become much more frequent. “As temperatures rise and summer rainfall decreases, conditions highly conducive to wildfire could be nearly five times more common in some regions of the UK by the latter part of the century,” he concluded. “In the driest regions, this could put habitats at risk for up to four months per year, on average.”

Image credit: Malachi Brooks (Unsplash)

Image credit: Google Earth

Image Credit: Northern Island Fire Service

Image Credit: Northern Island Fire Service

Image Credit: Northern Island Fire Service

Image credit: Almos Bechtold (Unsplash)

Image credit: Issy Bailey (Unsplash)

Banner image credit: Marty Galbraith