Some experts fear the triple whammy of climate change, urbanisation and population rise will result in catastrophic global hunger by the middle of this century. One possible solution is vertical farming. Ian Valentine asks if it’s time for agriculture to grow up.

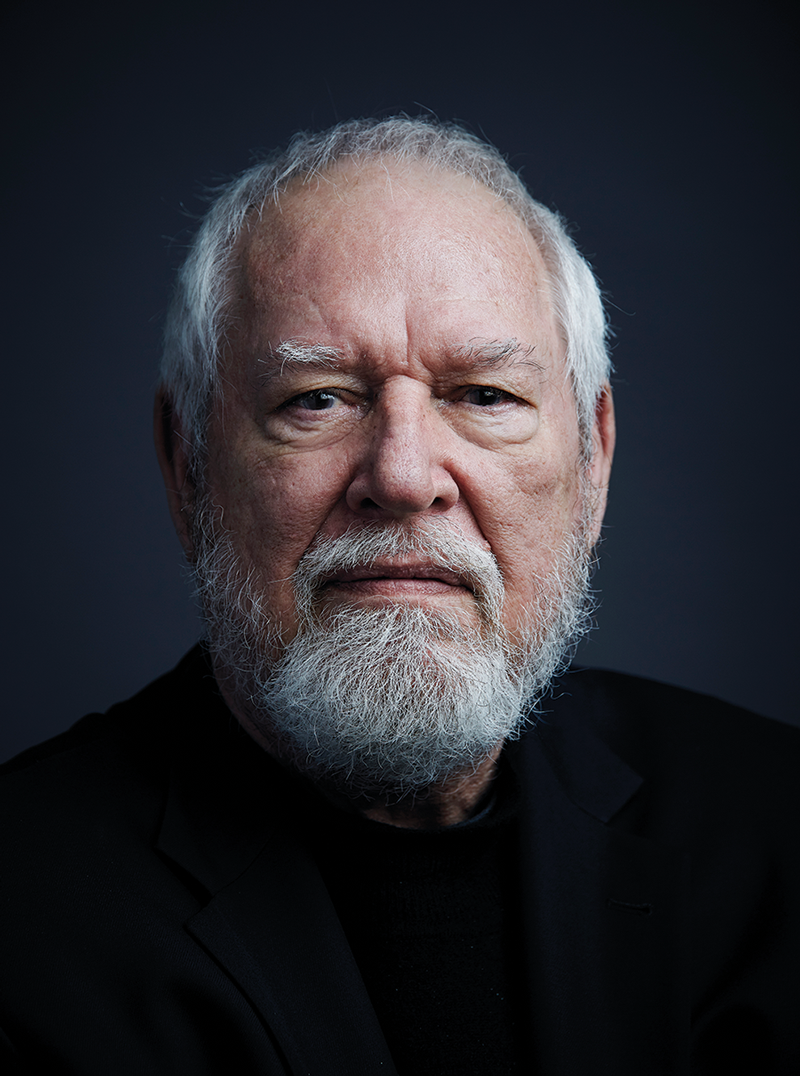

Dickson Despommier, professor of microbiology and public health at the University of Columbia, New York City, never tires of talking about his favourite subject. Recognised as the father of vertical farming – today, a fast-expanding industry where fruit and vegetables are grown in high-rise buildings rather than traditional rural fields or greenhouses – he recalls the moment the penny dropped in 1999.

“We were in the classroom, discussing the causes and possible solutions of climate change, and my students got downhearted. They said they felt powerless to make a difference. So, they embarked on a six-month practical to calculate how many Manhattans could be fed, if all of the borough’s rooftops were dedicated to gardening.”

Just two percent, was their answer. Negligible. Despommier tried to pick his students up off the floor. “It’s a good start,” he said, off the cuff. “But what if the interiors of those buildings were handed over to production too? How many people could be fed then?” He admits that question has consumed his thoughts ever since.

Among the many academic books Despommier has written is The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century. While he is not the only one to have championed the idea of urban farming, his enthusiasm, and his moniker, ‘vertical farming’, have given it a platform at a time when consumers and entrepreneurs are looking for alternatives to traditional agriculture. “This has gathered momentum because the planet is showing clear signs of disease,” he explains. “Mankind is now struggling to produce crops in once fertile lands that have become barren because of the changing climate. Look at how the monsoon patterns have shifted in southeast Asia or the Far East, for example, causing whole farming communities to fail, and then move to the cities. Millions of people have gone from producers to consumers in just a generation.”

As an academic, Despommier has scant commercial interest in outcompeting outdoor farmers. He sees his mission entirely in climate change terms. “If traditional agriculture was doing well, vertical farming would never have taken off,” he maintains. “The burning question for the human species is: what are we going to do when it’s no longer possible to grow the amount of food that we’ve grown before? What happens in a few decades’ time when there are 10 billion mouths to feed?”

On paper, certainly, the potential benefits of urban farming are compelling. Imagine year-round crop production, in which all four seasons guarantee a bumper harvest. Weather becomes irrelevant. Water can be saved and re-used. Desert, arctic or tropical regions can become self-sufficient in lettuces or chickpeas. No pesticides, fertilisers, or herbicides. No toxic agricultural runoff. No need for shipping or storage. New employment opportunities in neglected city areas, which often have a surplus of abandoned properties. Clear opportunities for wind, solar, tidal, and geothermal energy.

Above: Dickson Despommier is one of the world's experts on vertical farming, and author of The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century.